What Is Migration?

Most simply, “migration” is a mass movement, or a series of consecutive movements, from one place to another.

Many species of wildlife have annual or cyclical migrations. In North America, the most widely recognized of such migrations is in wild birds, including songbirds, raptors, shorebirds, and especially waterfowl—aka ducks, geese, and swans.

Let’s consider waterfowl migration within a calendar year.

January generally finds most North American ducks at the southern terminus of their range, which can be as far south as South America or as far north as Lake Michigan or coastal Maine, depending on the specific species. Good wintering grounds simply require ample food and water sources so ducks can survive the winter and build reserves for the northward migration in the spring.

Depending on species and conditions, northward duck migration generally begins in February, March, or April. Biologists believe the length of daylight influences the waterfowl migratory instinct to some degree.

In the spring, the movement tends to be sporadic, following the conditions favorable to the birds. Waterfowl tend to move northward as wetlands thaw and fields become free of snow. Snow geese, in particular, are known to “follow the snow line” and even turn back south when faced with heavy snowfalls that blanket the fields. They’ll generally move south only far enough to find food and water and then move north again with the melt.

During the northward migration, pair bonds continue to be created or strengthened for the upcoming breeding season for many species.

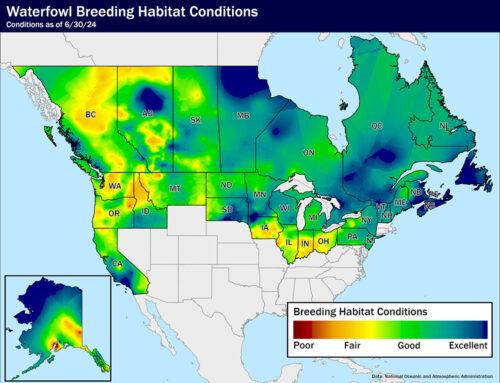

The goal of the northern movement is the nesting grounds, wherever those might be. For many duck species, it’s primarily in the prairie pothole region of northern United States and southern Canada. It’s estimated that up to 70 percent of the ducks hatched in North America begin life in the prairie pothole region.

Others, especially many goose species and ducks such as pintails, scaup, and eiders, go as far north as the arctic regions to establish breeding colonies. Arrival on the breeding grounds is generally from April into early June, depending on species, location, and conditions encountered.

Some waterfowl species nest where they winter, with little or no migration. These include some eiders, California mallards, so-called “resident” Canada geese, wood ducks, and others. Within these species, some populations make traditional, lengthy migrations, while others stay within one small area.

In all, a single spring migration from south to north may range from breeding right at the wintering location, or traveling up to 2,500 miles—again depending on the species and the preferred wintering and breeding grounds. The philopatric tendencies (or “homing” instincts) of waterfowl are amazing. It remains largely a mystery how some waterfowl can navigate the full cycle of migration over thousands of miles—sometimes repeatedly—and find their way back to the same patch of nesting cover in which they were hatched and/or which they used for nesting the previous year.

Overall, ducks spend about 90 days on the breeding/nesting grounds. And it’s a very important 90 days. It’s estimated that the conditions and situations the ducks encounter there have a 90 percent or greater influence on the overall population that will migrate north the next spring. That means everything that happens during the entirety of the remaining nine months—including hunting season—only impacts populations by 10 percent or less.

During their time in the North, waterfowl make mini migrations within the region. Waterfowl move to molt (shed and regrow new feathers—a period during which they a flightless) and then to gather again into larger flocks and prepare for southward migration. This is called “staging.”

Again, dependent on species and climatic conditions, southward migration tends to begin in September and can really gain volume and velocity in October and November. Long stretches of continual migration are more common as waterfowl move south in the fall, especially during major weather events. Pushed by weather and tailwinds, individual ducks have been known to travel 1,000 miles or more in 24 hours.

Climatic conditions play a major role in dates, distances, and locations to which waterfowl will migrate. Much about the migratory instinct of waterfowl remains a mystery, including exactly how birds navigate, especially to places they’ve never been before, as well as precisely what spurs migration and how much influence human activity such as agricultural practices, land development, light pollution, and other factors influence migration timing, patterns, and instincts.— Bill Miller

Leave A Comment