What Is Delta Predator Management?

Backed by more than three decades of carefully collected and analyzed data, Delta Predator Management proves to be the most effective and efficient tool for restoring “natural balance” in North America’s most important remaining waterfowl breeding habitat of the prairie pothole region.

“North America’s prairies have changed and are changing.”

This declaration may be the greatest understatement of all time. Yet it’s by no means stunning to anyone who’s paying attention—even a little.

It was the Greek philosopher Heraclitus who said, “The only constant in life is change.” Looking for something a bit more contemporary? Bill Gates put it this way: “We always overestimate the change that will occur in the next two years and underestimate the change that will occur in the next ten.”

When it comes to the North American prairies, the change over time has been massive, irrevocable, and—at least to some extent—unavoidable. This is particularly true for the portion we label “the prairie pothole region” or “North America’s Duck Factory.” Yet, if change is indeed the only constant in life, change to the prairies was and will always be inevitable.

Here’s a snapshot of prairies as they were in the past.

Prior to European settlement and ultimately today’s global human population of more than 8 billion people, the North American prairies were inhabited by some indigenous peoples but primarily by wildlife that played an important role in the land’s fertility. For millennia, prairie soils were tilled by the hooves of nomadic buffalo herds that came and went from specific areas, sometimes separated by periods of years before returning again to a precise location. The coexistence of the plants and animals native to the prairies represented a state that is sometimes referred to as “natural balance.”

Paradoxically, this balanced state was facilitated by the constantly changing environment on the prairies. Animals and vegetation adapted to cycles of abundant precipitation and severe drought, cycles of extreme cold and intense heat. Massive prairie fires cleared away dead grass and ground cover, transforming the tied-up nutrients to ash, which plants rely on for regeneration, and improving the habitat for wildlife. But as ideal as it was, this “natural balance” would be challenged and transformed by forces more determined and persistent than a prairie fire—European settlement and the North American farmer.

How Farming Changed the Prairies Forever

Beginning in the mid 1600s and through the late 1800s, European settlement virtually eliminated large carnivores and the buffalo. Farmers began tilling the soil for agriculture and instituted the commercial grazing of livestock to sustain not only the settlers themselves but growing urban populations who had become steady consumers of their agricultural commodities.

The stark reality of feeding an ever-growing global population has taken a toll on the prairie landscape. In hindsight, there may have been better, more forward-thinking ways to manage the prairies and prairie wetlands, but today’s reality is that they bear the irreversible changes brought about by both natural causes and by human beings who are cultivating and farming it to feed the growing population of the world.

Why Predators on the Prairies are Problematic

By the 1600s, saber-toothed cats and American lions were long extinct in North America, but grizzly bears and wolves still roamed the prairies. This was the last time the predator community was intact and regulated by nature at a broad scale in the continental United States and Canada. While most mega-predators are still present in North America, their populations and ranges have been negatively impacted by habitat loss and human interference.

For the safety of humans and their livestock, European settlers quickly began efforts to control predators, especially large predators. By the 1880s, bears and wolves, and other mega-predators had disappeared from the North American prairies. Absence of these mega-predators allowed meso-predator populations to flourish on the prairies. Meso-predators are mid-sized, mostly omnivorous, mammalian species, such as badgers, foxes, skunks, mink, coyotes, raccoons, and the like—all of which seek ducks, duck eggs, and/or ducklings for food.

In a state of “natural balance,” mega-predators tend to keep meso-predator populations in check. However, when mega-predators are no longer part of the system, whether from natural or human causes, the population of meso-predators will increase. More small predators in diminishing habitat means bad news for ducks!

Changes in land use and predator communities not only created opportunities for the expansion of existing meso-predator populations but spurred the invasion of meso-predator species not previously native to the northern prairies. A prime example is the raccoon. Raccoons did not even exist in most of the prairie pothole region before the 1950s! That fact defines exactly the kind of “change” and “imbalance” which we are talking about and which we are seeking ways to offset.

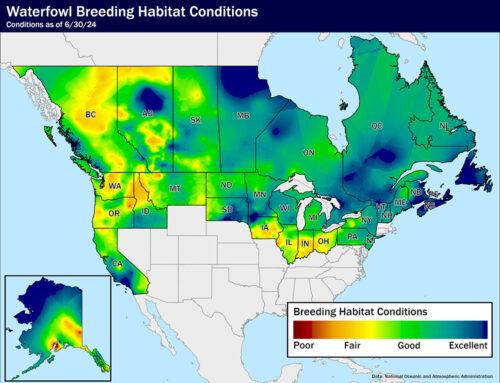

It’s important to note that the prairie pothole region, or PPR, is massively important to North American duck production. This wetland region in the heart of North America’s prairies is, in fact, nicknamed “The Duck Factory.” It’s estimated that in any given year, this region produces upwards of 70% of the wild ducks hatched in North America to fly down all four flyways as far south as this continent’s ducks migrate. In portions of the PPR, some areas have duck nesting densities as high as 60-100 pairs per square mile. That’s why reinstating natural balance in the PPR is so important.

Homesteading also changed the prairie landscape and impacted predator populations. This practice began in the southern parts of the prairies and plains and was prevalent in the northern US prairies and southern Canada in the late 1800s. As homesteading claimed nearly all parcels of land in the prairies, a rudimentary home was built on each homesteaded parcel. Homesteaders necessarily became highly efficient at removing meso-predators to protect their chickens and other livestock, effectively keeping the meso-predator population in balance as the mega-predators had previously done.

However, homesteaders and their descendants eventually learned that farming small parcels was not economically viable. Small properties were sold to neighbors; farms were consolidated; homes were abandoned. By 1930, the original buildings on many of the original homesteaded lands had been abandoned, and this trend continues today. Without landowners working diligently to remove predators from the prairies, these predator species once again thrived. Abandoned homes and outbuildings are perfect denning locations for both native and invasive meso-predators. Another change that impacted the predator population occurred with the arrival of the 1930s’ Dust Bowl era. Landowners, encouraged by government agencies, planted trees and windrows on the historically treeless prairies. Tens of thousands of windrows were planted for soil conservation. This planting of trees coincides with the range expansion of the raccoon.

Before the 1950s, raccoons were not even present in the southern prairies. However, due to the earlier removal of large predators, followed by the abandonment of human homestead structures and the planting of trees on the prairies, the population quickly grew to expand all the way to the boreal forest of northern Canada. It is the first and largest example of native predator community expansion in North America. Their story is an essential chapter in the ongoing tale of how change impacts “natural balance.”

Meso-Predator to Prey Relationship Is Not Symbiotic

The relationship between mega-predators and their preferred prey is often called “symbiotic,” meaning that their existence is mutually beneficial. In “Never Cry Wolf,” Farley Mowat wrote “…this is why the caribou and the wolf are one; for the caribou feeds the wolf, but it is the wolf that keeps the caribou strong.”

In that relationship, the mega-predator focuses primarily on the weak, the sick, and the old of the prey species. As a result, the wolves expend fewer calories acquiring food and face less risk of injury and death in the pursuit. The vitality of the caribou herd is boosted through survival and reproduction of the fittest.

Not so when it comes to the predator/prey relationship of, say, racoons and skunks to ducks. These meso-predators are completely opportunistic. If they find eggs, they eat eggs. There’s no discretion or selection of “bad eggs.” The predator expends few calories and faces virtually no physical risk. There’s no benefit to the vitality of the overall duck population; in fact, the hen of a predated nest expends more energy and undergoes more danger in renesting attempts, essentially weakening the flock.

More Changes that Increase Meso-Predators on the Prairies

Through the first half of the twentieth century, the commercial harvest of furbearers likely continued to suppress meso-predators. However, beginning in the 1980s, worldwide fur markets tanked, and so did the number of active trappers. The service that homesteaders, small-operation farmers, and commercial trappers provided to keep meso-predators “in balance” still continues to decline.

Proving this point, in 2018, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife actually halted the sale of fur trapping licenses due to the nearly non-existent demand for such permits. Because the management of the trapping/trappers in the state could not fund itself, the state bureaucracy that managed trapping ceased entirely. Public pressure had very little to do with the loss of trapping in California—it imploded from within.

Fur trapping north of the border has also declined precipitously. In Saskatchewan, from a mid-20th century peak of more than 25,000 licensed trappers, trapping license sales declined to fewer than 2,000 by the millennium.

The Threat Continues to Build

Another example proving that change to the prairies continues to effect meso-predator populations is the proliferation of the American opossum, which has expanded its range north in recent decades to include most of South Dakota. Large portions of South Dakota are prime waterfowl nesting habitat. Opossums love eggs. That’s a formula inevitably leading to even greater, and potentially devastating, imbalance.

Change to the prairies continues. The threats of meso-predators to native wildlife—especially ducks—continue to grow. It’s the duty and desire of the entire conservation community to seek ways to offset the change and restore natural balance.

Predator Management: One of the Tools in the Toolbox

We will never recover the wetlands that were drained over the decades nor the uplands that were put under the plow more than a century ago—at least to an extent that would be impactful in restoring wildlife habitat and populations to their former state. The old adage on the wisdom of real estate investment which says, “Buy land because they aren’t making any more of it” applies equally to prairie wetlands—nobody’s making any more of them! Despite anyone’s best efforts, even if they were backed by unlimited funding, we will never be able to reclaim enough lost wetlands to deliver any significant replenishment of the wildlife populations that depend on them.

The universal, cooperative focus of the conservation community must be on preventing any further loss of prairie habitats AND making those which remain as conducive to wildlife production—in our case, ducks—as they can possibly be.

If change is constant, inevitable, and irreversible, then efforts to accurately define “balance” in nature—let alone to restore it—are speculative at best. However, as conservationists who are willing to deliver time, talents, and resources to the effort, we can significantly impact the abundance of all wildlife species by maintaining the habitat that remains and strategically monitoring and managing their environment to allow them to be as productive as possible.

For more than three decades, Delta Waterfowl has been researching and refining ways to give nesting ducks a fighting chance against the onslaught of environmental changes that challenge their very existence every year when they return to the breeding grounds. Remember, it’s proven, accepted science that 90% of the events that impact duck populations occur during the approximately 90 days the birds spend in their prairie breeding habitats.

To positively impact duck populations, our efforts must be focused on the breeding grounds to optimize the productivity of the habitat that remains. Data collected from more than 30 years of Delta’s scientific research shows that the most effective, most efficient, and most scalable way to boost nest success and duck production in remaining PPR habitats is to counter the imbalances caused by human-generated change in the habitats through predator abatement and management. In the simplest terms, that is science-based, monitored, lethal predator control.

Trapper Ken Laycock sets a trap as part of Delta’s predator management program.

The type of predator control that Delta advocates is unique in that it focuses on carefully defined, highly targeted areas with the greatest potential for duck production. Delta’s goal is NOT to wipe out every meso-predator on every acre of the PPR. That would not be possible, scalable, nor desirable. It most certainly would not reflect natural balance, which is the goal.

Delta Predator Management is laser focused on areas of the highest duck nest densities because it’s in these locations where predator management has the greatest positive impact on duck populations. Focusing on these areas also makes Predator Management most cost-effective. Through this program, we benefit the most ducks for the lowest outlay of dollars, thereby best serving our donors and supporters, as well as the ducks.

To clarify, we are referring to lethal predator management—but no more so than was provided by mega-predators, homesteaders, farmers, and commercial fur trappers in the past. Delta’s Predator Management program is simply filling the void. In fact, because of the proven science behind Delta’s methods, we can reestablish the balance that existed decades ago in the most efficient way possible.

While Delta-style Predator Management impacts many meso-predator species in the precisely selected areas we choose to trap, even there our focus is on the most impactful predators—namely, racoons and skunks. In fact, Delta has conducted intensive research on the movement of racoons within and around wetlands seeking to optimize trapping efficiency. In all Delta trapping blocks, the primary focus is on catching as many meso-predators prior to the ducks’ arrival in the nesting area, as possible. Predators that are caught before the ducks begin laying never have the chance to destroy nests.

Just as there are multiple ecological and environmental benefits to conservation of permanent, semi-permanent, temporary, and ephemeral wetlands, Delta-style Predator Management likely benefits several other species of prairie wildlife. For instance, many species of ground-feeding and ground-nesting songbirds and upland gamebirds and other wildlife (including reptiles, amphibians, and mammals) share waterfowl breeding habitat in the PPR, and their numbers are dwindling—many more severely than waterfowl. A better balanced meso-predator population in their breeding, nesting, and denning areas could help increase their numbers, as well.

Delta Hen Houses Also Abate Predators

The Delta Hen House is a nesting structure used nearly exclusively by mallards. The cylindrical structure mounted on a steel pole several feet about the surface of water in a permanent or semi-permanent wetland puts the nest, hen, and clutch of eggs out of reach of most mammalian meso-predators. These Hen Houses are highly effective—often giving a hen mallard using a Hen House up to a 12 times greater chance of nest success than a hen nesting on the ground in nearby upland cover.

Obviously, the Delta Hen House is a highly efficient and effective predator abatement tool in boosting mallard production They are successful in protecting both the eggs and the brooding hens themselves.

Although Hen Houses are widely adopted only by mallards, Delta-style Predator Management boosts the production of many other species of ducks and has the potential to positively impact other upland and wetland prey species; turtles, for example. Ongoing research led by the University of Wisconsin – Whitewater has proven that raccoons love to eat turtle eggs as well as the soft, newly hatched terrapins. (More Here)

Predator Management Used Widely to Restore Natural Balance

While Delta’s Predator Management programs on the prairie is the most researched, documented, and continually refined example of predator control in the name of restoring natural balance, other efforts are achieving similar, favorable results. Lethal predator control is commonly employed in many, many situations across North America to help tip the scale in favor of at-risk prey species.

A few examples include:

- Sage grouse in Utah, Nevada, and Oregon – Active management of greater sage grouse in Utah (a species in danger of official listing as threatened or endangered) includes lethal predator management of avian species, such as ravens, as well as meso-predators including coyotes, and especially red fox and racoons. (More Here)

- Woodland caribou in Canada – Canada’s management plan for the northern mountain population of woodland caribou—which in many portions of its range is considered an at-risk species or worse—includes lethal predator management of wolves focusing on specific caribou populations.(More Here)

- Alaskan Moose and Caribou – Among the most important species for subsistence harvest in Alaska are moose and caribou. Populations of both have suffered significant declines in recent years. The State of Alaska has undertaken predator management, especially of the wolf population, in an effort to reduce the pressure of predation on these herds.(More Here)

- Mojave desert tortoises in southwestern S. – While human-caused change to habitat is the primary threat to the desert tortoise, predation by ravens and coyotes is viewed as an inhibitor to their recovery. Both direct, lethal predator control of ravens in targeted areas and programs to reduce the growth of raven populations in general are part of the USFWS “Revised Recovery Plan for the Mojave Population of the Desert Tortoise.” (Ravens have a major and growing predatory impact on many species of wildlife, including waterfowl. Current estimates of population growth for common ravens from the breeding bird survey show growth from 0.2 – 9.4% annually with the highest increases in the North American Deserts and Great Plains, respectively. Reasons include artificial nest substrates (transmission lines), cattle calving lots, increased roadkill, and open landfills. Efforts are underway to implement roadkill pickup as a mitigation strategy to offset golden eagle mortality that has potential to lower production of ravens, and to make transmission lines less attractive for nesting by ravens. Efforts are underway in Oregon, Nevada, and Utah to gain understanding of the effects the lethal removal of ravens.)(More Here)

- Multiple species of native wildlife threatened by feral swine population explosion – While the epidemic expansion of feral hog populations across the southern U.S. (and increasingly moving farther north) is most often thought of as a threat to property and agricultural enterprises, these omnivorous, destructive animals are also a threat to native wildlife species such as bobwhite quail, deer, and many more. Their primary threat to wildlife is the destruction of critical habitats and displacement from them. Virtually all states in which feral hogs are found have made lethal management efforts a high priority.(More Here)

- Multiple species of native fish threatened by silver carp invasion – In addition to the direct threat invasive carp species pose to humans by injury to those who use the waterways, their greater threat is to the critical habitat and food sources of native fish species. Both state and federal programs are in place to remove and ultimately eradicate these invasive species from America’s interconnected waterways. (More Here)

Winning the PR Battle

Though the numbers aren’t precise, consider for argument’s sake that 10% of North Americans are anti-hunting; 10% are hunters and support the causes of hunters. The remaining 80% fall in the middle and are, ultimately, the group who will decide the future of hunting and, thereby, the future of conservation in North America. The hunting community needs to make every effort to keep the views of the majority of the 80% on the positive side of the scale. We do this in many ways, but primarily through the messages we send to the non-hunting public through our words and our work.

When it comes to the general public’s support for “trapping,” the spectrum is far more disproportional. A significantly higher percentage of North Americans would label themselves as anti-trapping, and a very small (and rapidly decreasing) percentage are active trappers or pro-trappers.

A legitimate concern is that associating hunters with what the masses understand to be “predator management” via trapping will negatively influence the opinion of the 80% in the middle. This could be the case if science-based Predator Management aimed at restoring “natural balance” is not carefully and thoughtfully explained. In other words, it will take a concerted effort to ensure that all hunters and conservation groups are “singing from the same hymnal.”

Delta has done the science. When it comes to duck production, we have proof that our style of researched and refined predator management works. It makes the remaining prairie habitat more productive. It moves the needle toward restoring “natural balance” on an ever-changing prairie landscape. It arguably regains some of what was lost due to human-induced changes over hundreds of years.

There are many tactics that can be employed to educate the public about this strategy of achieving natural balance on the North American prairie. However, all of them are likely to be time-consuming and massively expensive. Time and money are vital resources that can be used to much greater effect in producing more ducks and—potentially—other prairie wildlife through predator management.

This is why Delta believes that the best course is to continue to expand our Predator Management program where it’s appropriate and most effective. When we are challenged for a rationale, we have the facts to defend what we are doing—that is, our use of scientifically proven technique to aid in the restoration of “natural balance” on an everchanging prairie.

Restoring natural balance on the prairies should be a goal shared by everyone in the conservation community. A shift toward Delta-style predator management is a key tool in the toolbox that would play an important role in delivering it.

To do this, we need to continue to transform attitudes toward predator management, attract scaled adoption and deployment by the broader conservation community, and establish a new paradigm that maximizes productivity and survival of waterfowl and other wildlife that are negatively impacted by overabundant meso-predators on the PPR and beyond.

Excellent article. We manage 300 acres of wetlands in NJ for waterfowl production and we’re the top wood duck producers. Not only do we heavily trap the mammalian predators to help nesting waterfowl, but we also manage the snapping turtles which are a huge factor in duckling survival. The first year we banded wood ducks we banded 54 ducks. 1 out of 6 had missing toes, webs, or feet from snapping turtles. The following year we banded 47 ducks and still one out of six had turtle damaged feet. These were just the lucky ones that escaped. We started trapping the snapping turtles and we removed 115 keeper turtles in the 300 acres. The following year the amount of ducks doubled and we banded 82 wood ducks and only 2 had damaged feet from snapping turtles. Managing snapping turtles is an absolute must to yield large broods oc ducklings. The following year we ended up banding 254 wood ducks for the state on that same property. Predator management is a must and don’t overlook the snapping turtle. They are a ducklings worst nightmare. Creating more duck habitat is also creating more snapping turtle habitat. You must also manage the snappers within that habitat.