Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey is Back in 2022

After two-year hiatus because of COVID-19, the important index of North American waterfowl populations was conducted in May

A lot has changed since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, but one thing that hasn’t: the need for data to inform waterfowl management and hunting regulations.

Season lengths and bag limits are adjusted annually based on changes in bird abundance and habitat condition. Since 1955, the Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey has provided that vital data. Conducted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Canadian Wildlife Service, this annual survey spans more than 2 million square miles of critical waterfowl breeding grounds. It’s the largest and most extensive wildlife survey in the world.

The annual evaluation of waterfowl population and habitat in North America has enormous practical importance for waterfowl managers and hunters. However, because of fieldwork limitations related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the full survey wasn’t conducted in 2020 or 2021. In May 2022, the survey was completed for the first time since 2019.

“It’s great that there will be a survey this year,” said Dr. Frank Rohwer, president and chief scientist of Delta Waterfowl. “This is a cornerstone piece of information that’s used to set harvest regulations.”

A Data Drought

In the absence of newer surveys, hunting regulations have been developed based on the 2019 data and habitat projections for 2020 and 2021. In 2019, the total number of breeding ducks was 38.9 million, 10 percent above the long-term average. Hunting regulation frameworks remain liberal across all four flyways for the 2022-2023 season.

USFWS has relied on mathematical models of population growth and decline to estimate current waterfowl populations. Despite these efforts, the breeding population remains uncertain without an up-to-date survey, especially on the tails of drought in the Prairie Pothole Region.

“We’ve had two lousy production years,” Rohwer said. “Ducks like to settle in the prairies, but when the prairies are dry, they will overfly and go other places. We don’t count them in those other places, so we could have ducks come out of the woodwork and populate the prairies.”

In 2019, duck production in prairie Canada languished due to dry conditions. That year, May ponds — a critical resource for breeding ducks — numbered just shy of 5 million, 5 percent below both the previous year and the long-term average. In Canada, pond counts were down 22 percent. Regardless, the ever-adaptable mallards made up the difference in the U.S. prairies, where conditions were excellent. That year, mallards exceeded their baseline by 19 percent, with a total breeding population of 9.42 million.

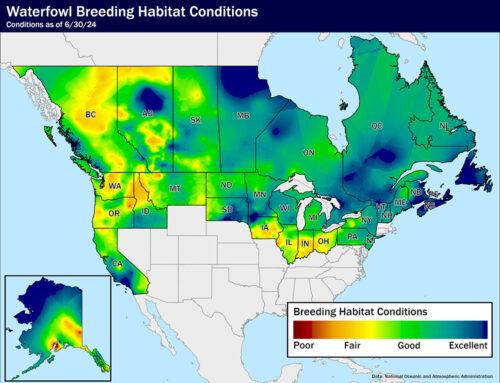

Many key breeding areas for ducks across the Prairie Pothole Region were in good to excellent shape in May, which is an encouraging sign for this year’s duck production, and, of course, for duck hunters.

Results of the 2022 Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey are expected to be released in August. — Anna Kottakis

In Central Oklahoma we had lots of April RAIN the local Canada Geese population will and has increased for 2022 early September Teal/Geese hunting. Plus speaking of Teal because of the WET Oklahoma rains a lot of TEAL were hanging around longer that EVER BEFORE. Happy 2022-2023 hunting BE SAFE!!

Norman, Oklahoma

Cleveland County