State Duck Surveys Offer Mixed News for Waterfowl Hunters

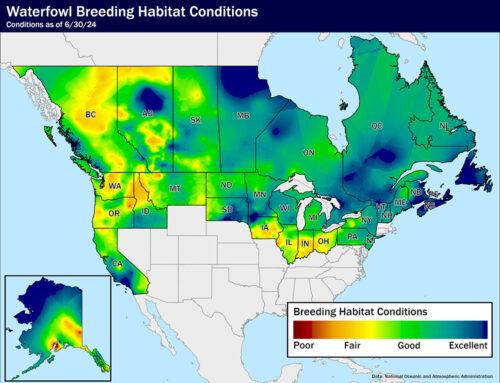

Given the cancellation of the USFWS Waterfowl Breeding Duck Population and Habitat Survey for a second year, surveys conducted by individual states are getting more attention than they typically would from duck hunters outside their regions. State biologists in North Dakota, Oregon, Wisconsin and Michigan have released survey results that offer a glimpse at what may lie ahead in this year’s fall flight.

News from the states is mixed. As is the case across much of the prairie pothole region, most breeding populations are doing well, but dry conditions likely prevented a successful spring for nesting ducks. However, goose hunters should be pleased, as resident honkers continue to thrive.

Here’s a summary of the reports.

North Dakota

Of vital importance to Mississippi and Central flyway hunters, North Dakota’s May survey includes a sobering data point: The water index (wetland count) is down 80.3 percent from 2020, putting it 66.7 percent below the long-term average. Given the drought sweeping North Dakota, it’s not surprising that the state’s breeding duck estimate is down nearly 26.9 percent from last year.

“This is the bad news we knew was coming,” said Dr. Frank Rohwer, president and chief scientist of Delta Waterfowl. “The reduction in water is staggering. It’s the highest percentage decrease in the history of the North Dakota survey.

According to Mike Szymanski, North Dakota’s migratory game bird management supervisor, 2020 was the sixth wettest year on record, while 2021 is the fifth driest in 74 years.

“That’s an indication of how dynamic this system is that we work in,” he said. “We essentially (had) no temporary and seasonal basins on the landscape (in May).”

More promisingly, thanks to strong carryover from previous productive springs, this year’s breeding duck index of 2.9 million remains 19 percent above the long-term average and is the 48th highest on record. And Canada geese are up 13.3 percent from 2020, with an estimated population of 379,786.

“There are still a lot of ducks,” Rohwer said. “The problem is I think this will be a ‘one and done’ year for nesting hens. There’s also a strong probability that duckling survival will be very low. It’s challenging to make ducks without water.”

North Dakota’s survey indicates decreases for all major species from 2020, including mallards, which fell 48.7 percent to 448,116 birds — the 28th highest estimate on record, but the lowest since 1993. Pintails fell to 81,716, a 65.9 percent decline and 67.7 percent below the long-term average. American wigeon declined 49.1 percent to 32,998, 15.4 percent below the long-term average.

There are certainly still plenty of teal. Though greenwings declined 49.6 percent to 34,710, they remain 70.3 percent above the long-term average. And bluewings fell 9.5 percent to just over 1 million birds, yet they’re still 42.4 percent above average.

Key diver species are in decent shape. Redheads declined 8.3 percent to 186,313, but remain a healthy 56.5 percent above the long-term average. Lesser scaup (bluebills) fell to 151,603, a 44.9 percent decrease that places them just above the long-term average. Canvasbacks, which nest more heavily in the Canadian prairies and parklands, declined 47.5 percent to 32,686, 19.6 percent below average.

Interestingly, the seemingly unflappable gadwall population continues to boom, increasing 47.4 percent to 649,216 ducks — an incredible 109.5 percent above the long-term average.

“Duck populations remain strong, but I don’t expect a ton of juveniles in the fall flight,” Rohwer said. “Experienced, adult birds are far tougher to decoy, which will challenge hunters — especially in Louisiana, Texas and other regions of the southern United States.”

Wisconsin

A survey of the Badger State indicates a similar situation: Plenty of ducks, increasing geese and poor nesting conditions. The total breeding duck population estimate of 522,546 is a 7 percent increase over 2020 and 19 percent above the long-term (47-year) average. Wisconsin’s breeding goose population has been stable to increasing for more than a decade — the 2021 estimate of 181,430 birds is a 3 percent increase and 68 percent above the long-term average.

However, Wisconsin’s mild, dry winter and below-average precipitation in April and May likely hindered the efforts of breeding ducks. Some may have benefitted from heavy rainfall later in May and June in certain areas.

“These varying conditions across Wisconsin mean we (were) at average- to below-average wetlands conditions for the year during the important brood-rearing period,” said Taylor Finger, Wisconsin DNR migratory gamebird biologist.

Of Wisconsin’s three species-specific estimates, only mallards showed a decline — down 5 percent from last year to 171,345, 4 percent below the long-term average. The blue-winged teal estimate of 65,124 is a 4 percent increase, but 37 percent below the long-term average. And wood ducks climbed an impressive 31 percent to 206,343, putting them 143 percent above the long-term average.

The estimate for “other ducks” — common goldeneyes, ring-necked ducks, green-winged teal, pintails, shovelers and more — is 105,042, a 17 percent decrease that remains 68 percent above the long-term average.

Michigan

Though it’s not a duck production mega-power like the prairie states and provinces, Michigan’s survey is arguably the most promising of those conducted this spring. The 2021 estimate of total ducks is 973,051, 191 percent above the 2019 estimate (no survey was conducted in 2020) and 58 percent above the long-term average. Meanwhile, the statewide water index is estimated at 505,033 wetlands, 16 percent below 2019 but 4 percent above the long-term average.

“Based on the water levels, wetland conditions were considered ‘excellent’ for breeding waterfowl statewide,” wrote survey summary authors Dave Lauukkonen of Michigan State University, and Michigan DNR biologists Barbara Avers and Sarah Mayhew.

The mallard estimate of 309,993 is 73 percent above the 2019 estimate, but 7.6 percent below the long-term average (since 1991).

Michigan’s Canada goose population continues to thrive as well. An estimate of 295,635 birds is 21 percent above the 2019 estimate and 27 percent above the long-term average. This marks the sixth straight year that the state’s honker population has exceeded Michigan’s long-term population goals.

Oregon

The good news: Oregon estimates a total duck breeding population of 260,056, up 3 percent from 2019 and just 1 percent shy of the long-term average. The bad news: The state is locked in drought ranging in scope from abnormally to exceptionally dry. While a survey of Alaska — a major feeder of the Pacific Flyway thought to have had good breeding conditions this spring — is forthcoming, Oregon had dismal conditions for duck production.

Still, breeding populations are in good shape. The gadwall estimate of 64,469 is a 14 percent increase and 21 percent above the long-term average. Northern shovelers climbed 34 percent to 28,717, 20 percent above the long-term average. Green-winged teal increased 46 percent to 8,452, 35 percent above the long-term average. And American wigeon increased 84 percent to 8,927, 41 percent above the long-term average.

Two major western species declined, but remain within striking distance of long-term averages. Mallards dropped 9 percent to 76,259, 16 percent below the long-term average. And cinnamon teal fell 18 percent to 26,609, 23 percent below the long-term average.

In keeping with a major theme this spring, Oregon’s Canada geese are up 13 percent to 53,795, 18 percent above the long-term average.

Look for further analysis from Delta Waterfowl coming soon, along with the annual “Fall Flight Forecast” in the Fall 2021 Issue of Delta Waterfowl magazine. —Kyle Wintersteen

Would be helpful if these articles were dated.