Seeking Solutions for Eastern Mallards

Groundbreaking Delta Waterfowl research aims to boost Atlantic Flyway populations

Whether coasting on cupped wings above Seneca Lake, the Susquehanna River or Back Bay, a sunlit flock of Atlantic Flyway mallards — their emerald green heads and chestnut breasts gleaming with color — is a stirring spectacle. It’s also an essential sight in terms of hunter success.

Mallards dominate duck straps in New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland and other northern and mid-Atlantic states, in some years accounting for one-third or even half the harvest totals for those states. Overall, mallards ranked second in the Atlantic Flyway’s duck harvest, behind only wood ducks (gunned heavily in Georgia and the Carolinas), in the 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 seasons.

However, if you reside in the East and haven’t been living under a pit blind, then you know there’s a problem: The northeast U.S. mallard population has declined sharply since 1998, prompting the Atlantic Flyway Council and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to reduce the daily bag limit to two mallards (one hen) for the 2019-2020 season. As a result, Atlantic waterfowlers have been looking for answers.

Delta Waterfowl is leading the charge to find solutions.

“The Duck Hunters Organization is hard at work for our members and waterfowl managers to get eastern mallards back on track,” said John Devney, senior vice president of Delta Waterfowl. “We are putting our money where our mouth is, and committed to answering key questions about Atlantic Flyway greenheads.”

In partnership with Dr. Michael Schummer of the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Delta Waterfowl is currently studying stable isotopes in the flight feathers of juvenile mallards shot or banded in the Atlantic Flyway. This groundbreaking science has the potential to reveal where the young ducks were hatched, allowing Delta to better understand the decline and identify the eastern mallard’s most critical breeding areas.

The goal, ultimately, is to use the information to boost production of eastern mallards, better inform wildlife managers setting harvest regulations, and hopefully, pave a way to increase the Atlantic Flyway bag limit.

“Our goal isn’t just cool research, but strong, actionable science that matters and should hopefully be applied,” Schummer said. “For most people on the East Coast, the mallard is the No. 1 duck in the bag. We need to solve this problem, or we’re in trouble.”

Delta Waterfowl is researching the eastern mallard decline in partnership with Dr. Michael Schummer, left, of the State University of New York.

Delta Waterfowl is researching the eastern mallard decline in partnership with Dr. Michael Schummer, left, of the State University of New York.

Eastern Mallard Mysteries

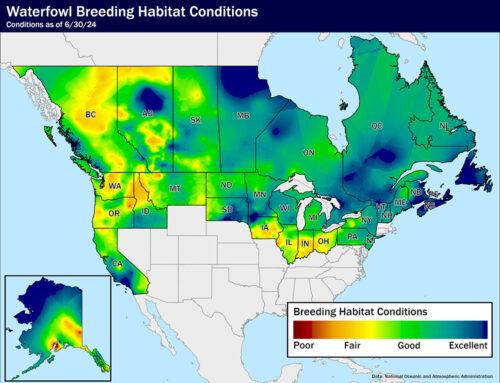

Conservation challenges faced by the USFWS and state biologists include the existence of two separately surveyed breeding populations of eastern mallards — those that nest in the northeast United States (New Hampshire to Virginia) and those that breed in the eastern survey area (eastern Canada plus Maine).

Here’s what’s clear: Ground-plot surveys indicate that mallards breeding in the northeast United States have been declining by about 2 percent per year for the past two decades (despite a 17 percent increase in the 2019 survey to 565,000 ducks). This is the population that led the USFWS to halve the Atlantic mallard limit.

Meanwhile, aerial surveys denote that eastern Canada’s mallard population has been steady to increasing, although it declined slightly in the 2019 survey to 484,800.

Combined, the two populations put the 2019 eastern mallard breeding population at 1.05 million birds, 16 percent below the long-term average and down from a high of 1.42 million in 1998.

Beyond these numbers, mysteries abound: in particular, why an adaptable, highly productive species has steadily declined in the northeast United States.

“What’s fascinating is that the best available data on eastern U.S. mallards suggests that we’ve got a declining population with stable production and stable survival rates,” Devney said. “That doesn’t add up. We can certainly look at pintails or bluebills and see what’s driving their population declines, but we can’t answer that basic question about eastern U.S. mallards.”

Further, little is known about the regions and habitats of eastern Canada that have allowed the historically non-native mallard to gain a foothold. In the prairie pothole region, Schummer says, this lack of fundamental science would be unthinkable.

“The Atlantic Flyway has taken a distant backseat in the waterfowl world,” said Schummer, an avid duck hunter. “There’s a mallard-shooting culture in the mid-continent and so that ends up being the focus to a large degree.”

The unknowns surrounding the eastern-mallard decline fueled a discussion between Schummer and Devney at the Atlantic Flyway Technical Section Meeting in September 2018. They agreed that Delta Waterfowl — a grassroots-funded organization with an unrivaled research legacy — and Schummer’s renowned SUNY lab could make a strong partnership.

Stable isotope research soon came into focus.

“Conversations with the Atlantic Flyway technical staff made it clear they had two major research priorities: Determining the relative contributions of eastern Canada versus eastern U.S. mallards to hunter harvest, and gauging the annual production rates of each eastern mallard population,” Devney said. “That would improve their understanding of the overall eastern mallard decline and better inform future decisions on hunting regulations. Stable isotope research can answer both questions.”

The stage was set for Delta Waterfowl and SUNY’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry to work toward improving eastern mallard numbers.

Innovative Research

Stable isotopes are biological markers locked in certain bodily elements, such as human hair and waterfowl feathers. Their analysis is a rather recent scientific breakthrough with a variety of applications, including the ability to determine where a duck was hatched with surprising precision.

“We could do stable isotope work on your hair or fingernails, and I could tell you what types of food you’ve been eating and where you ate them,” Schummer said. “It’s all tied to precipitation patterns, which give a specific signal as water gets broken down into other molecules that bind elsewhere in the body. So if the signal is 38, the latitude of Virginia, then that means the bird was produced in Virginia.”

Schummer has been hard at work collecting a wing feather — specifically, the tenth primary — from as many juvenile mallards as possible.

Schummer and eight graduate students plucked a feather from each of the 650 samples collected at the conclusion of last spring’s Atlantic Flyway “Wingbee,” an annual USFWS event in which wings voluntarily submitted by hunters are used to approximate the species, sex and age composition of the hunter harvest. Later that summer, boxes of quarter-inch primary-feather clippings arrived from Connecticut, Pennsylvania, New York, Vermont and Massachusetts, obtained during summer banding research by Schummer’s colleagues.

Schummer and eight graduate students plucked a feather from each of the 650 samples collected at the conclusion of last spring’s Atlantic Flyway “Wingbee,” an annual USFWS event in which wings voluntarily submitted by hunters are used to approximate the species, sex and age composition of the hunter harvest. Later that summer, boxes of quarter-inch primary-feather clippings arrived from Connecticut, Pennsylvania, New York, Vermont and Massachusetts, obtained during summer banding research by Schummer’s colleagues.

Collecting feather samples from live and dead ducks increases the sample size, thereby enhancing the efforts of Schummer and Delta to identify key mallard production areas and compare the duck production of eastern Canada versus the northeast United States. Further, the dead-duck samples will reveal whether the U.S. Atlantic Flyway harvest is disproportionately filled by one of the two managed eastern mallard populations. In other words, are Americans shooting mostly local birds, a high number of migrants or a mix of both? And the feathers clipped from live birds could improve banding data by providing an additional window into each duck’s origins.

None of these processes are inexpensive.

“If it wasn’t for Delta, I wouldn’t even have had enough funding to go to the Wingbee, let alone begin my research,” Schummer said. “Delta had the capacity to find the funding and jumpstart the work.”

Schummer’s team spent the next year painstakingly logging samples, sending them to nearby Cornell University for formal stable-isotope analysis, and charting the results. He knows the stakes are high, both in terms of reversing the eastern-mallard decline and staving off a potential further loss of hunter numbers in the Atlantic Flyway because of conservative mallard-harvest regulations.

“The sky isn’t falling, but in terms of mallard bag limits, right now we’re in the ‘safe zone’ phase until (the USFWS gets) more information,” Schummer said. “Decisions are being made based on pretty simplistic models and limited data. I always hate it when we’re playing everything safe for the birds because the hunters matter, too.”

Early Findings

Like all good scientists, Schummer is careful to avoid drawing conclusions based on incomplete data. However, the initial year of data hints at a powerful suggestion: Eastern Canada’s breeding mallard population may be larger — and more productive — than anyone believed.

“We found a pretty strong signal for Canada with one year of data,” Schummer said. “That’s where the mallards were coming from to a very large degree. Whether the second year will tell us the same thing, I don’t know, but the lion’s share of productivity came from Canada, not the northeast United States.”

Additionally, Schummer hypothesizes that mallards produced in Canada are arriving in the United States earlier than assumed, and in turn they might be falsely identified as northeast U.S. mallards during September banding operations. That would be problematic, because it would mean banding data is underestimating the size and production of eastern Canada’s mallards. On top of that, band-return data would suggest that hunters are shooting a larger portion of the northeast U.S. mallard population than they actually are.

A reduced daily mallard limit has left Atlantic Flyway hunters looking for answers. Delta is leading the charge to find solutions.

So, while stable-isotope research isn’t intended to replace banding — one of the most important tools available for tracking populations and survival rates — it could help improve its accuracy.

“The banding data will tell you that the mallards shot here are coming from the states, but the initial stable-isotope data says something different,” Schummer said. “So, while New York says 68 percent of the mallards it shoots were produced within the state, a way to say it more accurately might be that 68 percent of the banded ducks shot in New York were banded in New York. We don’t yet know for sure if or to what extent this is happening, but we’re going to get there.”

Years of research lie ahead. But let’s just assume that through good, careful science, the first year’s results continue to replicate themselves. That could change everything for waterfowl managers and Atlantic Flyway duck hunters.

Stable isotope research is revealing key eastern mallard breeding areas — data that could boost the population and pave a way to increase the Atlantic’s daily mallard limit.

“It may prove that we have far fewer breeding mallards in the northeast United States than we believe, and that Canada has way more than we think, plus good production,” Schummer said. “We may not have a problem. We may not have a mallard problem in the East at all. This is stuff we’re going to be able to get at eventually. It might take longer than we’d like, but the waterfowl community has solved one problem after another, and I think we’ll figure this one out.”

Delta Waterfowl is committed to seeing this eastern mallard mission through to the end.

“Delta is in this for the long haul,” Devney said. “We intend to contribute good science to understanding the eastern mallard decline, and to help establish extremely well-informed hunting regulations. The Atlantic Flyway technical committee has a lot of work in front of it given the new reality with eastern mallards and the flyway’s recent multi-stock regulations-setting process. That’s why, for ducks as well as duck hunters, this research is so critical.”

Delta Waterfowl managing editor Kyle Wintersteen hunts eastern mallards in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania.

Leave A Comment