Delta’s Drone Traveler

Researcher Roald Stander searches for nesting birds using innovative science

By Paul Wait

Roald Stander’s ascension as a pilot has been a whirlwind experience. Literally.

The 29-year-old University of Manitoba graduate student, who only recently became a certified drone pilot, has flown across the United States and Canada in search of nesting birds on behalf of Delta Waterfowl.

The 29-year-old University of Manitoba graduate student, who only recently became a certified drone pilot, has flown across the United States and Canada in search of nesting birds on behalf of Delta Waterfowl.

“I’m a quick learner. I had to learn on the fly,” he quipped.

Delta Waterfowl first tested the use of thermal-imaging cameras mounted on drones as a method to detect nesting ducks in May 2016. After the initial drone testing showed great promise, Delta sought student researchers to study the application not only to find nesting ducks, but also upland game birds, songbirds and shorebirds.

Stander, who was a wildlife technician for Delta in 2016, became interested in drones when he learned about Delta’s testing. Soon after, under the guidance of Delta and his adviser, Dr. David Walker, he began working toward becoming a licensed drone operator and understanding thermal technology.

This spring, loaded with a brand-new drone, an expensive thermal camera and extra batteries packed in a hard-sided case, Stander’s bird detection tour began.

He traveled to South Dakota to search for nesting pheasants, which can be tough to find using traditional nest searching methods because the hens simply run away from the nest — rather than flush — or squat low to hide.

Stander jetted to North Carolina, where the goal was to find nesting black ducks. There, weather conditions proved difficult, with high temperatures and humidity hampering the ability of the camera to see the ducks in grass.

“We had a hard time finding ducks, but it worked incredibly well for finding Virginia rails,” he said. “This is pioneering research. There are a lot of potential avenues for thermal research to be used in wildlife management.”

Stander was disappointed that the black duck portion of his work didn’t turn out better in the limited timeframe there, but he said the experience added valuable knowledge about finding ducks using drones.

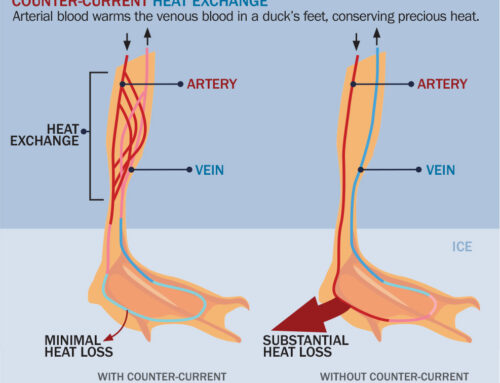

“Ducks are more difficult to detect because they are better insulated and their bodies radiate very little heat,” he explained.

However, duck feathers reflect the sun, and the contrast is detected by the thermal-imaging cameras.

Often, a duck nest that might otherwise go unnoticed is detectable because the bowl of warmed eggs show up on screen, even when the hen is sitting on them, Stander said.

“Incubated eggs really glow,” he said.

Stander’s tour took him to Manitoba, where he used his drone to find and survey sharp-tailed grouse dancing on their leks. He bounced over to Alberta, where he flew his drone to find Hungarian partridge. He searched for piping plovers there, too.

He traveled to North Dakota, again searching for upland-nesting ducks — this time it was mallards, gadwalls, pintails and teal. And then it was back to Manitoba, where he provided valuable technical assistance to Jacob Bushaw, another Delta research student who was working with drones and thermal cameras to detect over-water nesting ducks such as canvasbacks, redheads and ring-necked ducks.

“The biggest thing is the challenge of the weather,” Stander said. “Software is a limitation, too. As the software improves, efficiency will improve. Long-term, the cost of using drones for research should be lower.”

“The biggest thing is the challenge of the weather,” Stander said. “Software is a limitation, too. As the software improves, efficiency will improve. Long-term, the cost of using drones for research should be lower.”

Stander has clearly become comfortable piloting drones, and has developed a keen eye for what he’s seeing on the screen. By flying in multiple locations and in an array of weather conditions, he’s learned to compensate for environmental factors, too.

Many of Stander’s flights have been conducted at night — often predawn — because the temperature differences between birds and the vegetation is greatest after the landscape has cooled down.

“What has been surprising to me is the variability in detectability of birds,” Stander said. “One night you’ll see 1,000 rocks, and the next night at the same spot, you don’t see any rocks at all and can see a partridge at 400 yards.”

Drone and thermal technology could increase efficiency over traditional chain-dragging methods, said Joel Brice, vice president of waterfowl and hunter recruitment for Delta Waterfowl.

In that method, a long, heavy chain attached to a pair of all-terrain vehicles is pulled through nesting cover. The chain rolls over the grass, bumping the hen off of her nest. After the flush, the technicians follow the chain and conduct a physical search to find the nest.

“We accept the idea that with chain dragging, you’re not finding all of the nests,” Brice said. “The thought is that the drone is going to find more nests than the chain method. It should be more efficient. You don’t need two ATVs and you don’t need a truck to haul them around.”

In addition, some bird species are difficult to find because they hide their nests well and use diversion strategies to lure predators — and researchers — away from their eggs. Other birds simply nest in remote or difficult terrain to access on foot.

In addition, some bird species are difficult to find because they hide their nests well and use diversion strategies to lure predators — and researchers — away from their eggs. Other birds simply nest in remote or difficult terrain to access on foot.

“Using drones has real possibilities when you look at it from a manpower perspective,” Stander said. “You can save cost and time, plus you don’t have the disturbance of vegetation and wildlife that is caused by dragging a chain.”

Having flown through his first nesting season as a drone pilot, Stander is eager to continue to learn more about nesting birds and how to find them.

“I’m really thankful for the opportunity to be put out on the forefront of this research,” he said. “I’m doing everything I can to make it work.”

Paul Wait is editor and publisher of Delta Waterfowl.

Thank you for everything you do Delta! I support DELTA Waterfowl!