Bird Flu Outbreak Update

Number of detected cases in wild birds has dropped, but HPAI still present

By Paul Wait

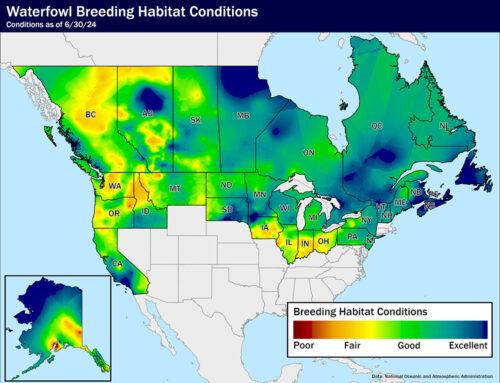

As the 2023-2024 waterfowl seasons get underway throughout the United States and Canada, hunters should again be aware that highly pathogenic avian influenza, or HPAI, continues to sicken and kill migratory birds.

The good news is that the prevalence of the deadly bird flu virus might be decreasing.

The current HPAI outbreak was first detected in North America late in 2021, with cases reported in all four migratory bird flyways across the United States and Canada. HPAI has been confirmed in more than 7,150 wild birds during the past two years. Many of those birds died from avian flu.

Dr. Andy Ramey, research geneticist at the U.S. Geological Survey Alaska Science Center, said cases of HPAI in wild birds are still trickling in.

“HPAI is still around, but we’re not sure at what level because there’s not a ton of mortality right now,” Ramey said during an interview in late July. “The number of detections has declined somewhat markedly this year compared to the same timeframe in 2022.”

USGS and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service continue to closely monitor HPAI, testing waterfowl and other birds during summer banding efforts. In addition, sampling of hunter-harvested waterfowl for HPAI will resume in September.

“Now that these viruses have occurred in wild birds for a fair amount of time, there could be some immunity in the population,” Ramey said. “Some birds may have developed antibodies to fight or survive the infection. Some of the underlying occurrence of HPAI may be masked by that. Another unknown is what will happen when hatch-year birds start to congregate for migration. What will happen this fall is still very much unclear.”

The first known HPAI outbreak in North America that affected wild birds was detected in November 2014 in the Pacific Flyway. By June 2015, that outbreak had dissipated. From August 2016 to November 2021, no cases of HPAI were documented in North American wild birds.

HPAI has primarily afflicted farm-raised poultry. Millions of chickens, turkeys, and other captive birds died as a result of HPAI in domestic flocks in 2022. The prevalence of HPAI caused egg shortages and a resulting spike in egg prices and related bakery goods.

According to the Center for Disease Control, the threat of HPAI to human health remains low. A poultry farm worker in Colorado contracted HPAI in 2022, but that person was involved in depopulating an infected flock. The worker exhibited flu symptoms and recovered. No other cases of HPAI affecting people have been reported in North America.

A case of HPAI resulting in the death of a pet dog in Oshawa, Ontario, made news in April. The dog was chewing on an infected goose. The case prompted the Canadian Food Inspection Agency to issue an advisory not to feed raw meat to pets. HPAI cases in dogs are rare, with no other documented cases of severe HPAI infections during the current outbreak.

Hunters should follow common-sense precautions while handling wild birds. Wash your hands after hunting, wear protective gloves while field dressing birds, don’t eat, drink, or smoke while handling birds, and sanitize game-processing areas. For more information, visit https://fws.gov/avian-influenza.

While afield, Ramey cautions hunters not to handle any birds that are obviously sick or found dead. Birds infected with HPAI might exhibit symptoms such as swimming or walking in circles, inability to fly, and a lack of coordination.

“HPAI is likely still in populations of birds that are being hunted and in wetlands that are being hunted, so hunters should be mindful of that,” Ramey said. “If something seems odd or there seems like there could be a disease event, please report it to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or the state management agency. Those observations are really important and help our science move forward.”

American hunters traveling to Canada are allowed to bring game bird meat into the United States but must follow U.S. Department of Agriculture importation guidelines. A USDA memo issued Aug. 3 https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USDAAPHIS/bulletins/368d413 details that all game birds must be cleaned, stored, and transported as follows:

- Viscera (innards), head, neck, feet, and one wing must be removed. In a change from 2022 guidelines, skin can now be left on.

- Feathers must be removed, except on one wing—as required by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for species identification.

- Carcasses must be rinsed in fresh, clean, potable water prior to packaging and must be free of dirt, blood, or feces.

- Carcasses must be chilled or frozen, placed in clean leak-proof plastic packaging, and stored in a leak-proof cooler or container.

- Cooked or cured game bird meat will not be allowed to be imported.

Hunter-harvested wild game bird trophies entering the United States from Canada must be fully finished, or accompanied by a VS import permit, or consigned directly to a USDA Approved Establishment. Hunters may find an approved taxidermy establishment by visiting the Veterinary Services Process Streamlining search page and searching for a taxidermist with the HPAI product code in your state.

Leave A Comment