An Awakening

A week exploring the prairie breeding grounds brings revelations about ducks, research and hunting

By Anna Kottakis

Growing up in the New Jersey suburbs, my exposure to hunting dead-ended somewhere around Elmer Fudd. In high school, a boy I was dating shot a squirrel with a BB gun from his back porch. I cried and broke up with him two weeks later.

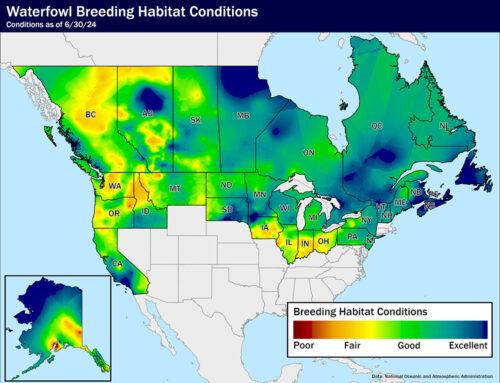

It took a lot of time (and a fair bit of luck) for my idea of a hunter to include more than cartoon characters and teenage boys. But somehow, this June, I found myself driving through North Dakota in a Delta Waterfowl truck, its decals proclaiming me a part of The Duck Hunters Organization. As Delta’s communications intern, I was headed to Manitoba, Canada, to be immersed — literally — in the wetlands where so many North American ducks start their lives.

As the miles (sorry, kilometers) passed by, the same checklist cycled hypnotically through my thoughts. Gas? Waders? Camera? Check, check, check. A nagging sense of misbelonging? Check. Big-time. The closer I got to Delta’s field research station, the surer I was that everyone — the field staff, my coworkers and maybe even the ducks themselves — would know I was a fraud (dare I say… a quack?). Sure, I could write about policy, predation and nest success percentages, and I loved doing it. But for all the fascination hunting held for me, I didn’t really understand it, or the people who do it.

By 7:15 the next morning, philosophical quandaries had been swept aside by something a lot murkier. My first day of shadowing Delta’s field technicians found me waist-deep in pond water and cattails. My right arm extended stoically overhead — à la Statue of Liberty — to keep my borrowed camera dry, while my left windmilled wildly to swat mosquitoes and maintain a semblance of balance.

I was following (from a farther and farther distance, due to my sluggish progress) Delta’s field techs while they splashed and squelched into wetland after wetland to find duck nests. When they do, they record its GPS coordinates, the number and species of eggs, the eggs’ stage of development and the appearance of the nest.

It’s valuable data painstakingly collected. As a lifelong athlete and regular hiker, I thought I’d have no problem keeping up. I was wrong. It was the first in a series of surprises the prairie had in store for me.

The second was a canvasback hen flushing from only a few feet away from me. The third was the field techs themselves.

Take crew leader “Canvasback Zach” Peck. He can grab mosquitoes out of the air Karate Kid-style and move easily through the same matted cattails that keep me in super slo-mo. At first, he seemed exactly like the “hunters” of my stereotyped imagination.

“Oh man, last year? I shot a looooot of ducks last year,” he remembers, lapsing into a contented silence. I’m a few seconds away from counting the charismatic 22-year-old as another tally for “trigger-happy” when he slams on the brakes.

“Look!” he says excitedly, pointing to a roadside pond that looks, well, just like every other small wetland we’ve been in and out of for the past seven hours. In the backseat, another field tech and I stop dozing long enough to see what he’s pointing at.

Paddling happily across the surface, there’s a ruddy duck. It looks just like every other one I’ve seen this week. But I’m seeing something new — Zach himself. Even with three summers of fieldwork experience and a lifetime of hunting, he stops the car just to look at a ruddy duck. He might love hunting ducks, but he loves the ducks, too.

All three of us are grinning and giddy. It’s the first moment that I start to get it — something I know now is called “the hunter’s paradox.”

It’s a lot like nest searching. Once I know what to look for, it’s a lot easier to see.

Each day, after searching a certain area, or “block,” the field techs check on previously located nests. In the weeks of my internship leading up to this trip, I learned and repeated Delta’s facts about predation: That management can boost duck production by 80%, that predators such as raccoons are overpopulating the prairies, that Hen Houses can take nest success from under 10% to over 60%.

But the statistics don’t prepare me. Prairie Canada is pastoral, peaceful and jaw-droppingly picturesque. But it’s a difficult place to live — and stay alive — if you’re a nesting duck or worse, a duck egg.

“Oh no,” Hannah Sabatier said, crestfallen. As usual, I’m a few steps behind the Manitoba native. When I catch up, I find her standing over a nest that’s half torn-apart and littered with eggshells. It’s our fourth nest check, and the third she’s found predated.

“That was one of my favorite nests,” Hannah says quietly as we splash back toward the shore.

It’s sobering. Even in the best habitat a North American duck can hope for, there’s no guarantee of survival. In fact, even here, the odds are stacked against them.

After three days with the field techs, I take my new perspective (and 67 mosquito bites… yes, I really counted) to Portage la Prairie. What started with a few episodes of MeatEater, curiosity and an impulsive internship application was starting to crystallize into something more. I didn’t know it then, but if there’s anything that’ll foster — hell, even demand — a duck obsession, it’s the Delta Marsh.

And, of course, the people who work there. I got to spend the first half of my day in a side-by-side with Amanda Szadkowski, a member of the Marsh staff for five years. Amanda doesn’t have a can-do attitude: She has an “it’s-done-before-you-ask” attitude.

Luckily for me, she’s patient, too. I spent those hours asking all the questions I could think of about predation, hunting, habitat, rainfall and ducks.

Around midday, the whole staff came together for lunch at Kirchhoffer Lodge. Before the rest arrived, Amanda showed me a short essay on the wall describing the building’s historic past. The humble red building had hosted the greatest minds of waterfowl science – Hochbaum, Leopold and all their successors. It wasn’t just at the center of prime duck breeding grounds: It was at the core of Delta’s founding and mission.

That’s when it hit me. It didn’t matter, really, how little I knew now or how I ended up working for The Duck Hunters Organization. What did matter is that I was here. I had the opportunity to learn from this place and these people.

(Which is not to suggest anything so cliché as “there are no stupid questions.” There are definitely stupid questions. And I asked a lot of them. Early on in my trip, I pointed innocently at a coot and asked, “What kind of duck is that?”)

I spent most of the weekend — my final two days — meandering through the trails. I brought my camera and my duck ID book, trying to sneak up on nesting ducks to either take a picture or to practice identifying them. I’m still better at the former, but there’s time to learn, and plenty of knowledgeable and passionate people to learn from.

So yeah, I spent a week in Manitoba drinking the Kool-Aid. On the drive back to the United States, I replayed Delta’s podcast series, which I had used as prep materials before starting my internship. Before, I had zeroed in on science and statistics while listening: my comfort zone. This time, I tried to keep all the context: The prairies, the nests, the history and yes, the hunters. Hunting, in real life, is a lot less cartoon and lot more conservation than I could’ve ever imagined.

Anna Kottakis, Delta’s 2022 summer communications intern, is a senior at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

AK, thanks for taking us landlubbers into this wondrous part of the Earth, where the searching turns out to be for our souls. What a fantastic and mind-opening experience.