Restoring Our Refuges

Delta's plan to recharge public habitat and revive waterfowl migrations

By Paul Wait

Once the crown jewel of waterfowl management in the United States, the National Wildlife Refuge System has slipped into disrepair because of deep reductions in staffing and maintenance budgets.

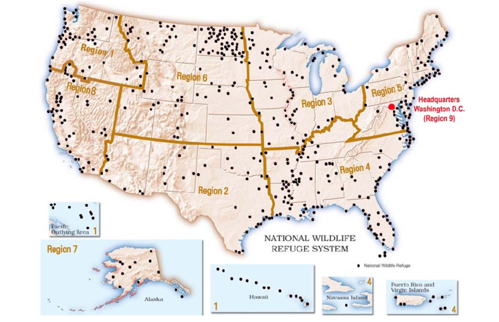

The 573 national wildlife refuges throughout the United States, which encompass 95 million acres of land and 760 million marine acres, serve as critical assets for the continent’s waterfowl and waterfowl hunters. Refuges provide important waterfowl nesting habitat in the prairies and other key breeding grounds, as well as foraging and loafing habitat along migration routes and at wintering areas. In addition, U.S. federal refuges host hunters for an estimated 2.6 million days each year.

The benefits of federal refuges to ducks and duck hunters diminish when staff shortages and trimmed-down budgets don’t allow for annual habitat work such as brushing, controlled burning, managing water levels, and other key property management functions, said John Devney, Delta’s chief policy officer.

The problem compounds when there’s not enough money to maintain and repair dikes, levees, pumps, and water-control structures.

“Those things fail just like our highways fail, just like our bridges fail, just like our railroads fail,” Devney said. “We’ve been in this decline of resources for waterfowl and wetland management. It becomes a double whammy when your infrastructure is failing at the same time you have less people to do the work.”

Recognizing the importance of national wildlife refuges to duck hunters, Delta is launching the Restoring Our Refuges initiative, a multi-pronged plan to increase funding and resources to boost the value of public lands for waterfowl.

Scope of the Problem

Our National Wildlife Refuge System was established by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt in 1903 on Florida’s Atlantic Coast, a 5,400-acre parcel known today as the Pelican Island NWR. In 1908, Roosevelt added the Lower Klamath NWR on the California/Oregon border as the nation’s first waterfowl refuge.

The NWR System has expanded ever since, largely powered by duck hunters. More than 300 refuges were acquired wholly or partially using revenue from the Federal Duck Stamp Program, which has raised more than $1.3 billion since 1934. The Duck Stamp and NWR System stand as one of the world’s most successful conservation initiatives in the world, providing incredible benefits to migratory birds and wildlife.

The 573 national wildlife refuges throughout the United States encompass more than 855 million acres—critical assets for the ducks and duck hunters.

--

Not coincidentally, the NWR System functioned well during the 1970s, when more than 2 million duck hunters took to fields and marshes across the United States. Duck Stamp sales peaked at 2.4 million during the 1971-72 season.

“If you go back 40 or 50 years, the state and federal refuges were the best-managed properties out there,” Devney said. “We’ve seen a seismic shift because we’re investing less in our public trust assets.”

The decline in our NWR System—particularly for ducks and duck hunters—has occurred over decades.

“Over the past 20 years, there’s been this silent, slow, steady erosion of quality happening on refuges that has become more and more visible,” Devney said. “It took some time to understand the impact and consequence of this change.”

Funding in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service budget to operate the NWR System has declined 35% or more since 2010. The NWR System has lost 711 full-time staff since 2011, a 29% workforce reduction. To compensate, many NWRs have been clustered into complexes to stretch staff over several refuges, resulting in decreased time and ability for biologists and staff to manage habitat effectively on each property.

“To keep refuges running well, you need efficient water delivery and fairly intensive management to maximize moist soil productivity,” Devney said. “In too many cases, there’s not the staff or infrastructure to do it.”

During the Covid-19 pandemic shutdown in early 2020, Devney and Ed Penny of Ducks Unlimited worked together to quantify the problem. They developed a list of infrastructure needs and found more than $250 million in “deferred maintenance” on priority waterfowl and wetland projects within the NWR System. Over the broader NWR System, the shortfall of unmet needs was an estimated $2.6 billion. It’s likely that both deficits have increased since 2020.

Working Toward Solutions

Armed with information, Devney and Delta raised the issue with legislators.

“During the first Trump Administration, there was widespread bipartisan support to deal with failing infrastructure needs,” Devney explained. “But nobody was thinking about refuges or wildlife management areas in that context. They were talking about airports and rail, ports and harbors, and highways and bridges, but we perceived there was a moment that maybe we could advance this conversation. At the same time, we heard murmurs about the Great American Outdoors Act and the Legacy Restoration Fund.”

The Great American Outdoors Act, which passed both branches of Congress by large margins, was signed into law in August 2020. Importantly, it authorized funding of $90 million a year from 2020 to 2025 to the USFWS for refuges.

“Our spreadsheet of deferred maintenance needs was ultimately one of the key things to get the Federal Refuge System funding included in the Great American Outdoors Act,” Devney said.

Unfortunately for ducks and duck hunters, waterfowl and wetlands were not prioritized when those funds were allocated to USFWS projects.

Undeterred, Devney and Delta continue to work toward improving the NWR System.

The current legislative focus is working to advance the America the Beautiful Act, a bill introduced by Montana Sen. Steve Daines that would authorize $100 million annually for seven years to fund NWR improvements.

“Not only do we need the (America the Beautiful) legislation to pass, we’re also going to have to work with the agency to ensure a significant chunk of the money is dedicated for the very reason we started the refuge system—for the benefit of migratory birds,” Devney said.

Delta is also advocating to give the USFWS the authority to use contracted services to perform work at refuges. Right now, unlike the Bureau of Land Management and other federal agencies, USFWS is not legally allowed to use third-party contractors for refuge-management work. If the USFWS was granted that authority, the agency could then hire outside help such as a local duck club manager to help clear brush, manage water, maintain moist soil units and do other management work.

“We have to find a way to help address that manpower need to manage habitat,” Devney said.

Southern Consequences

The impacts of a degraded NWR System are felt throughout the country, but they’re being magnified in the South by changes in land use during the past couple decades.

In the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley, a major migration corridor and wintering area for ducks, agricultural crops and the practices to grow food have evolved. The area, a floodplain of the Lower Mississippi River, includes Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana, four of America’s largest rice production states. Texas and California also rank in the Top 6 states for rice production.

Flooded rice fields provide high-value food to wintering waterfowl, attracting millions of ducks and geese every fall and winter. These same fields offer important hunting opportunity to thousands of waterfowlers.

According to U.S. Department of Agriculture data, rice production has declined since 2010, particularly in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas. In 2010, Arkansas, the nation’s No. 1 producer, had 1.79 million acres of rice fields, which dropped to 1.28 million in 2025. Louisiana’s rice acreage dropped to 482,000 acres in 2025 from 540,000 in 2010. Rice acreage was down dramatically in Mississippi from 305,000 acres in 2010 to 165,000 acres this year. Missouri and Texas also saw declines in acres planted in rice.

Along with fewer acres in rice production, agricultural practices have shifted away from leaving rice fields flooded to decompose the straw. A reduction in post-harvest flooding of rice fields dramatically reduces the available wintering habitat for ducks and geese, as well as opportunity for hunters.

Without a strong, well-managed refuge system to attract and hold waterfowl in historically important wintering areas, the birds shift to other areas. It becomes a duck distribution problem, often leaving duck hunters looking at empty skies.

“We need our public trust assets—state and federal—to work better than ever to meet that broader change in landscape architecture,” Devney said.

Louisiana hunters are impacted by another recent agricultural change: Thousands of acres of the state’s rice fields have been converted to sugarcane crops. In 2010, Louisiana had 420,000 acres in sugarcane production. In 2025, the USDA reports 525,000 acres of sugarcane in Louisiana. Sugarcane fields do not provide any habitat or food value to waterfowl, and no duck hunting opportunities, either.

Coastal erosion and hurricane damage to state and federal refuges has also changed duck distribution along the Gulf Coast.

The White Lake Wetlands Conservation Area, a 71,905-acre state-owned property in Vermilion Parish, Louisiana, provided critical winter habitat to hundreds of thousands of ducks before it was battered by hurricanes. Once the property was deluged with salt water, White Lake’s value to waterfowl, wildlife, and hunters plummeted.

Delta volunteer Brandon Broussard of nearby Abbeville, Louisiana, relentlessly championed the revitalization of White Lake until his death in 2023. Delta has continued to advocate for White Lake. Earlier this year, Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry allocated $29 million to rebuild levees and preserve key marsh habitat. The first phase of project calls for construction of 20 miles of rip rap along the Great Intercoastal Waterway to keep saltwater out and prevent erosion.

“This work represents the culmination of years of hard work and conversations between Delta Waterfowl, our volunteers and leadership from Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries,” said Cyrus Baird, vice president of government affairs for Delta Waterfowl. “This funding and future work will be critical to ensuring White Lake remains an important destination for wintering waterfowl and duck hunters alike in southwest Louisiana.”

Delta’s New Initiative

Delta Waterfowl is launching Restoring Our Refuges, an advocacy campaign to work on securing public funding to revitalize the health and waterfowl value of federal waterfowl refuges and state-owned wildlife management areas throughout the United States.

A key goal of the Restoring Our Refuges initiative is to increase funding for refuges in the federal budget and to work with Congressional appropriators to ensure the money is spent to improve wetland and waterfowl habitat.

“It’s about improving habitat, but it’s also about significantly improving hunting opportunity,” Devney said. “Since the majority of the federal refuges were acquired using duck stamp dollars, and duck stamp dollars come from duck hunters, those resources should go back to ducks and duck hunters.”

Delta will continue to work with local and regional USFWS staff to increase waterfowl hunting opportunities on priority refuges.

“When we talk about hunting opportunity, the value is in opportunity to high-quality habitat,” Devney said. “It’s not just being able to go through the gate, it’s going through the gate and having a chance to see and shoot a few ducks.”

Restoring Our Refuges will enlist the help of Delta’s chapter volunteers to amplify the effort.

“We’re asking our members and volunteers to help engage in this topic to help drive the investment back into public lands—both at wildlife management areas and refuges,” Devney said.

By using Waterfowl Heritage Funds, a Delta program that invests in local conservation projects, chapters can help improve habitat and hunting opportunities in their regions.

“Chapters have opportunities to engage in addressing problems and opportunities they are seeing very visibly in their back yards,” Devney said.

Jason Tharpe, Delta’s chief executive officer, was invited to the White House on Sept. 4 to meet with Doug Burgum, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior. Burgum and other senior leaders listened to input from Delta Waterfowl and other leading conservation organizations regarding the management of public lands.

“The discussion emphasized aligning conservation outcomes with federal land management priorities,” Tharpe said. “Delta Waterfowl was at the table to ensure the perspectives of waterfowl hunters were represented and heard.”

Tharpe, a native of Louisiana, keenly understands the perspectives and challenges of being a southern duck hunter.

“I lived through the 1990s and it’d be easy to call that time the last great period for duck hunting,” he said. “It was pretty phenomenal. Thanks to good water and CRP (Conservation Reserve Program) acreage, everybody seemed to be having very successful seasons, but in the background were the beginning of declines in our WMAs and refuges. I’m not sure we saw them as quickly as they were happening.”

Delta certainly did recognize the declines in numbers of duck hunters and has always understood the funding mechanism connection of hunters paying for waterfowl conservation.

“I think we’ve only recently woken up to understand how bad things are for public hunting lands,” Tharpe said. “We’re talking about a legacy of conservation. As waterfowl hunters, our refuge system is the flagship.”

Restoring Our Refuges is a major effort to improve waterfowl hunting throughout North America by investing more resources into our public lands.

“It’s a challenge,” Tharpe said. “I think it’s a matter of putting some attention to it and getting our policy makers focused on the right things. I think we’ve lost a bit of focus on game management in North America, and it’s been replaced by ecosystem management, species at-risk, endangered species management. Those are valuable things. But we need game management. It must be part of the system, especially in a system largely supported by hunters. Delta Waterfowl is committed to leveraging our resources to ensure it happens.”

Paul Wait is communications director for Delta Waterfowl. Article originally published in Delta Waterfowl's winter 2025 magazine.

Join Delta Waterfowl to receive our member-exclusive magazine and eNewsletter—packed with the latest in duck research, expert tips on duck dogs, hunting insights, conservation updates, and more.

Your membership helps you stay informed while supporting the future of waterfowling. Join now: Become A Member.