Hunt Ducks, Lose the Guilt

What does the science say about the impact of hunter harvest on waterfowl populations?

BY CHRISTY SWEIGART

Waterfowl populations are incredibly complex. And whenever survey numbers show declines of any sort, social media conversations and tailgate talks can quickly turn to: “We need to give those ducks a rest!” and “If we just closed the season for a couple of years, they’d bounce back!”

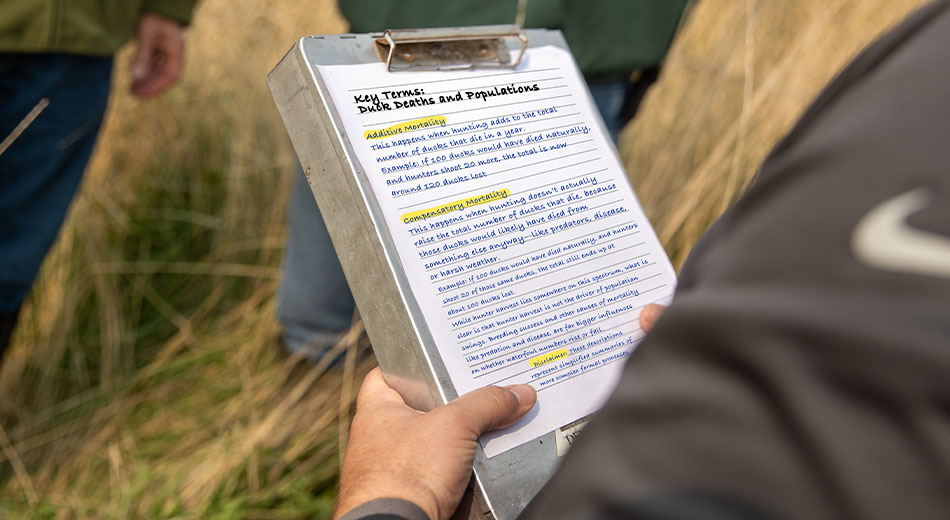

These statements come from the best of places, from people who care about safeguarding the resource. But science has shown that hunter harvest is actually one of the smallest parts of the equation when it comes to the rise or fall of most waterfowl populations. How? First, familiarize yourself with the terms at right, on the clipboard. Then, let’s delve into the data on hunter harvest.

Long-Term Science

For many decades, beginning in the 1950s, waterfowl managers largely operated under the assumption that hunting mortality was additive (see graphic, right). If a hunter shot a duck, it stood to reason that this added to the overall death rate—one more death stacked on top of all the natural losses ducks face. This assumption shaped the models that informed seasons, bag limits, and overall waterfowl management decisions.

But in the 1970s, new data and analysis shifted what waterfowl scientists thought to be true. Research suggested that hunting might not always add to the total death rate. That hunting mortality was largely compensatory, that it might replace other deaths that would have happened anyway due to natural causes, at least for some species. Today, through frameworks like Adaptive Harvest Management, managers are still studying and refining this spectrum, using banding data, breeding survey results, and advanced modeling to better inform management decisions.

At the forefront of this work is Dr. Todd Arnold, senior scientist for Delta Waterfowl. A veteran field biologist, Arnold has a unique ability to analyze large data sets and is dissecting more than 70 years of waterfowl data to better understand this spectrum and how hunting fits into the survival equation.

Drakes vs. Hens

A clear example of the complexity of hunter harvest is in the taking of drakes compared to hens. There is no one-size-fits all answer because of how different each species is.

“When we are talking about this topic, I would start off by saying that the harvest of drakes has no impact on the population and might actually be good for the population given the distorted sex ratios we have,” said Arnold. “Mallards, for instance, have a surplus of males compared to females. Because they are monogamous in nature, those extra drakes that do not find a mate often disrupt pair bonds or compete for resources without contributing to reproduction.”

So, taking more drakes may actually ease pressure on females during the high-stress breeding season.

“Harvest of males at current levels, or even if we increased it twofold, would have no impact and might have a positive impact on the population overall,” he said.

Hens have their own equation. Adult females drive reproduction, so their survival matters more.

“For most species, our hunter harvest rates for hens are so low that there’s still not much of an impact,” said Arnold. “We sometimes worry about pintails and yet we’re only harvesting around 3% of the adult females. We aren’t concerned about harvesting females in the big picture—we actually need to harvest them to estimate survival, abundance, and reproductive success. But compared to all of the other factors that kill hens, hunting does not have much of an influence.”

Life Expectancy

Looking at life expectancy helps us to understand why this is.

“Most of our dabbling ducks don’t live for very long,” said Arnold. “For species with the lowest survival like wood ducks or blue wings, they would only survive long enough (1.4 more years) to nest one more time, on average. For our larger dabbling ducks like mallards or pintails, they would survive long enough to have two more breeding seasons on average.

When survival rates get higher, like for some species of diving ducks, geese, and swans, then individuals have a longer life expectancy, so they could have many more breeding seasons, and that is where there is a much greater potential for overharvest. But, at the end of the day, hunter harvest is still the smallest of all the components that we can put a finger on.”

So, that doesn’t mean hunting has absolutely no effect, but the additional survival time lost when hunters take birds is miniscule compared to the many other risks ducks face.

“It’s important to remember that not all species are alike,” said Arnold. “Mallards and teal are short-lived but highly productive. Their populations rely on producing lots of young each year because most adults won’t survive long anyway.”

That’s why a one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t work and why different species have their own unique management approaches. Yet, for nearly all species, the key to improving their populations lies in improving the survival of hens and their nests on the breeding grounds each spring.

Predators on the Breeding Grounds

Another perspective comes from comparing hunting to other causes of death. Research has shown that hen mallards have about a 55% chance of surviving each year. Telemetry studies on the prairie breeding grounds have shown that roughly 25% of hens die during the breeding season, with nearly all of those losses occurring from predation on nesting hens. That is a rate about 4 to 5 times higher than losses to hunting.

Predation pressure has only grown over the past decades, with species like raccoons—which did not even exist in the prairie pothole region before the 1950s—expanding into the critically-important breeding grounds. If hunter harvest accounts for 5-10% of hen mortality, but predators account for 25%, then focusing on Predator Management—a proven tool that Delta has researched, refined, and implemented for more than three decades—can make a much greater difference in boosting duck numbers.

This highlights a central truth: Research across multiple species consistently shows that waterfowl populations are driven by “fecundity,” by the ability of hens to successfully nest and raise broods, rather than by the small percentage of ducks taken by hunters.

‘Give the Ducks a Rest’

So, if we go back to the questions hunters keep asking: When waterfowl numbers are down, should we close the season and “give the ducks a rest”?

The science says that while hunting does remove birds, it’s not the factor driving overall population declines or increases. Causes such as predation, disease, and other natural agents exert far greater pressure on their ability to survive.

“Yes, harvest is an important responsibility that we have to manage, and hunters certainly messed up 100 to 150 years ago in terms of market hunting and overharvesting,” said Arnold. “But the data is showing us that the percentage hunters harvest is so small that it’s not moving the needle very much, and that making the breeding grounds more productive each spring is where the real difference can be made. This is the type of research and analyses that will continue to inform our models for waterfowl management into the future.”

Christy Sweigert is an associate editor of Delta Waterfowl. Article originally published in Delta Waterfowl's winter 2025 magazine.

Join Delta Waterfowl to receive our member-exclusive magazine and eNewsletter—packed with the latest in duck research, expert tips on duck dogs, hunting insights, conservation updates, and more.

Your membership helps you stay informed while supporting the future of waterfowling. Join now: Become A Member.