Why Are Ducks Thriving … as Other Birds Decline?

Three words: investments by hunters

By Kyle Wintersteen

The familiar autumn chill graces your neck as you pitch your decoys, each one striking the water with a satisfying smack. In the darkness, your ears catch a staccato of wingbeats beckoning from above. Mallards, silhouetted in the moonlight—the first ducks you’ve seen in weeks. Maybe this will be the morning. Approaching the end of your 30-day season, perhaps in a few hours you’ll be clutching a long-sought three-duck limit.

You read correctly.

This bit of science fiction is offered as a cautionary, albeit imaginary tale of what life would be like if waterfowl populations mirrored the trajectory of America’s non-waterfowl bird species. Were that the case, one in four breeding ducks—25 percent of the population—would be gone. Mid-continent breeding mallards would number just 5.9 million (25 percent below reality’s long-term average), a mere few hundred thousand away from a continent-wide season closure.

In this nightmare scenario, the restrictive seasons of 1979 to 1987 (look it up, fellow millennials) would have never ceased. Shooting of canvasbacks, pintails, bluebills, wood ducks, black ducks, and all manner of sea ducks would’ve wavered between severely limited and closed. Multitudes of duck hunters would have, in turn, hung up their waders for good, which is why you’d be yet again sipping coffee in a duck boat, alone. Sure, fewer hunters would mean less competition for birds, but a lot of good that does when the season ends in the blink of an eye and well before the migration peaks.

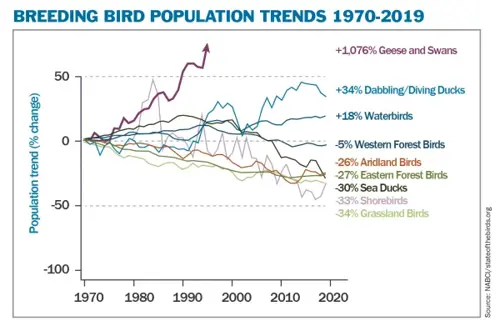

OK, snap out of it! Real life may have its problems—inflation, sky-high gas, and a ruler in eastern Europe with shark eyes and an inferiority complex—but if you’re a North American duck hunter, you’ve still got it pretty good. According to the 2022 U.S. State of the Birds report, overall dabbling and diving duck populations have increased 34 percent since 1970, while geese and swans are up a staggering 1,076 percent.

Waterfowl Up, Other Birds Down

However, in the report—produced by a group of public and private organizations led by the North American Bird Conservation Initiative—there’s a grave disparity. Namely, while ducks and geese continue to thrive, most other populations of American bird species are plummeting.

Some of the report’s more alarming trends include:

An estimated 3 billion fewer individual birds exist in the United States today than in 1970, and more than half of bird species are declining.

Grassland birds are among the fastest declining, with a 34 percent decrease.

Seventy species are trending toward the endangered list.

The biggest single threat to America’s birds is habitat loss. Others cited include invasive species; predation, specifically by domestic cats; and climate change.

Thank a Hunter

“I firmly believe that the conservation mindset of duck hunters is why waterfowl are not in the same unfortunate situation as so many other species of North American birds,” said Dr. Scott Petrie, CEO of Delta Waterfowl. “Over the past century, duck hunters have faced conservation crossroads numerous times, and they’ve always shown up whether the need was financial or at the ballot box. This is clearly evidenced by the 2022 State of the Birds report, and further justification for Delta’s critical mission to produce ducks and secure the future of waterfowl hunting in North America.”

Here at The Duck Hunters Organization, it’s easy to give our fellow waterfowlers a pat on the back for helping ducks to thrive even as other birds decline. More surprisingly, however, the report has inspired birders and other conservation voices—folks who aren’t necessarily against hunting, but probably wouldn’t know a Benelli from a Browning, either—to heap praise upon our ranks.

“Without the hunting and fishing community, (waterfowl) would have had the same trajectory as all these other species,” Ruth Bennett, an ecologist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute’s Migratory Bird Center, told Smithsonian magazine. “Hunting groups and federal agencies recognized that these birds were declining and took action. It’s really a conservation success story and it goes to show what’s possible when there is enough money and political will to protect birds.”

The Audubon Society, American Bird Conservancy, Cornell University’s Lab of Ornithology, Scientific American magazine, and others all noted waterfowlers’ long-standing contributions to conservation in their coverage of the State of the Birds report.

“Hunters were the original conservationists, starting the movement as we know it today in the late 1800s and early 1900s,” Petrie said. “There were few if any birdwatchers or other outdoor recreationists back then. It was hunters who recognized the challenges faced by waterfowl and other wildlife, lobbied for regulatory changes, and kicked in their own money to help ensure today’s flourishing migratory bird populations. Many non-hunters are unwilling to recognize this legacy or simply unaware of it, but the astute see it. Many birders long for a funding model that can achieve for songbirds what hunting’s done for waterfowl.”

Conservation Milestones

By the turn of the 20th century, ducks, geese, swans, and other migratory birds were reeling from habitat losses and decimated by the gluttonous free-for-all that was the market hunting era. Recognizing the crisis, sport hunters championed two acts of Congress that proved forerunners of today’s regulations.

On May 25, 1900, President William McKinley signed the Lacey Act, which authorizes the Secretary of the Interior to restore game and birds in regions of the United States where they’ve become rare, and regulates the introduction of non-native species. Perhaps most notably, however, it ended the market gunning era—waterfowl could no longer be killed by the thousands and shipped via rail car to snooty restaurants in Baltimore, New York, and Chicago.

The Lacey Act was soon complemented by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which protects birds that migrate between Canada, the United States and Mexico, prohibits the killing of migratory birds without the proper permit(s), and authorizes the Secretary of the Interior to set hunting seasons—a then-new concept that’s today taken for granted as in the best interest of waterfowl.

It was in 1934 that American waterfowlers made one of the rarer requests in the annals of human history: a voluntary tax—specifically Duck Stamps—to fuel historic investments toward the health of ducks and geese. Congress obliged by passing the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act, which has since raised $1.1 billion and protected more than 6 million acres of wetlands in the National Wildlife Refuge System. The effort helped inspire Canada’s Wildlife Habitat Conservation stamp (a.k.a. duck stamp), which since 1985 has invested nearly $56 million in nearly 2,000 conservation projects across Canada, including Delta’s Duck Production and HunteR3 initiatives.

A conventional assumption into the 1930s was that the larger the body of water, the more valuable it was to nesting waterfowl. However, leading-edge research by early Delta Waterfowl scientists soon demonstrated that in reality, small, shallow, ephemeral wetlands are truly the engines that drive duck production. Indeed, later studies at the Delta Duck Station revealed that 10 one-acre wetlands produce 10 times more juvenile ducks than one 10-acre pond. This discovery—coupled with concern over the more than 6 million acres of wetlands drained from Minnesota and the Dakotas following World War II—inspired an amendment to the “Duck Stamp Act” in 1958. The Small Wetlands Acquisition Program has since allowed the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to use Duck Stamp monies to purchase easements from willing landowners in Minnesota, Montana, and the Dakotas, to the tune of more than 1.5 million acres of critical prairie potholes.

“The Small Wetlands Program is arguably the U.S. government’s greatest conservation achievement in terms of benefitting nesting ducks and duck hunters,” said John Devney, chief policy officer for Delta Waterfowl. “Its success is why, in the 1990s, Delta began advocating for the Canadian government to adopt a similar program.”

Today easements are available to farmers and ranchers in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario. But the United States got a 40-year head start.

“On the U.S. side, the government could over the long-term reasonably conserve 45 percent of the prairie’s vulnerable, duck-producing wetlands before opportunities to acquire further easements fizzle,” Devney said. “But it’s unlikely any entity will be able to conserve half that many wetlands in prairie Canada, where easements are delivered by conservation organizations. The United States has had the advantage of a larger coffer of Duck Stamp money, and a vast number of prairie Canada’s small wetlands had been drained when easements became available.”

Decades later an agreement between farmers and the American public known as “Swampbuster”—a conservation provision of the U.S. Food Security Act of 1985—was reached. The contract promises that farmers and ranchers adhere to basic wetland conservation practices in exchange for taxpayer-funded federal farm program benefits, such as crop insurance and subsidies.

That same year, Congress included the Conservation Reserve Program in the Farm Bill. Administered by the USDA, the incentive-based initiative encouraged farmers and ranchers to restore perennial grassland habitat—the preferred nesting cover of mallards, pintails, blue-winged teal, and other dabbling ducks. The 2018 Farm Bill capped enrollment at 25 million acres for 2021 and 27 million by 2023. At peak enrollment (35-plus million acres), CRP added about 2.2 million ducks to every fall flight.

“The impact of CRP lands on duck production in the prairie pothole region can’t be overstated,” Devney said. “It’s especially evident when we hit dry periods like we’ve experienced in recent years.”

As CRP found its footing, in 1989 Congress passed the North American Wetlands Conservation Act—a funding mechanism for the visionary North American Waterfowl Management Plan established in 1986. A partnership between the USFWS, non-profits, and state/provincial governments, the program awards U.S. federal grants—each dollar of which must be matched by non-federal sources—toward conserving wetlands for migratory birds and other wildlife. Having conserved more than 30 million acres since inception, NAWCA received record funding at $50 million within the 2022 federal omnibus.

“Delta strongly advocated for NAWCA’s increased funding, given the massively consequential, positive outcomes it creates for ducks and duck hunters,” Devney said.

Delta-style Conservation

Delta Waterfowl has long worked with landowners to conserve the most essential and at-risk breeding duck habitats—shallow wetlands and prairie grasslands—starting with its Adopt a Pothole program in the mid-1990s.

“Ninety percent of the ducks hatched in the U.S. portions of the PPR come from private lands,” Devney said. “These are valuable farms and ranches, and they aren’t for sale. But we’ve learned that farmers are more than happy to help us make ducks when they’re provided a fair incentive.”

After years of demonstrating the capabilities of this voluntary, incentive-based habitat strategy to work for both ducks and the agriculture community, the Delta model was recently adopted in the United States (Working Wetlands) and Canada (Growing Outcomes in Watersheds).

Launched as a North Dakota pilot study in 2015, Delta’s Working Wetlands left an indelible mark on waterfowl conservation when it was included in the 2018 Farm Bill. Enrollment opened in April 2020 for landowners in the Dakotas, Minnesota, Iowa, and Montana.

“Working Wetlands is a monumental win for ducks and duck hunters,” Petrie said. “It targets the small, temporary, and seasonal wetlands that Delta’s earliest research tells us are the most critical to duck production.”

Delta remains hopeful that Working Wetlands will secure its federal funding goal, which if properly implemented, would protect up to 56.7 percent of small wetlands (more than 366 million acres) in the U.S. prairies and support the breeding efforts of up to 1.02 million ducks.

“That would easily make Working Wetlands one of the most consequential small wetland conservation programs ever delivered in the PPR,” Petrie said.

Delta’s advocacy efforts have also resulted in a commitment by the Manitoba government to secure 90 percent of the province’s most important wetlands for breeding ducks. The incentive-based program, Growing Outcomes in Watersheds, is directly inspired by the success of Working Wetlands. In late summer 2019, Manitoba doubled its investment in GROW, creating new incentives encouraging landowners to conserve wetlands and providing stable, perpetual funding.

“Delta hopes Alberta and Saskatchewan consider adopting a GROW-type approach as well,” Petrie said. “That would affect large-scale wetland and waterfowl conservation across the Canadian portion of the PPR.”

Million Duck Campaign

Announced in 2022, Delta is embarking on a mission to fill every flyway by applying nearly a century of duck production and habitat conservation research. Once operational, Delta’s Million Duck Campaign will add 1 million ducks to every fall flight, every year.

“The Million Duck Campaign is a colossal effort that’s unprecedented in waterfowl management,” Petrie said. “No one has ever achieved duck production on this scale. It will be great for duck populations, and for duck hunters.”

While the primary focus of the MDC is duck production, it will expand program delivery across all four Delta pillars.

Duck Production—Delta will strategically increase its annual duck production through Predator Management and Hen Houses to add 1 million ducks annually.

Habitat Conservation—Delta will continue to create programs and champion policies that conserve critical habitat for breeding ducks.

Research and Education—Delta will further pioneer waterfowl research to increase duck production, inform management decisions, and train future conservation leaders.

HunteR3—Delta will expand the organization’s work to recruit, retain, and reactivate duck hunters through First Hunt and the University Hunting Program, while also Defending the Hunt anytime, anywhere, as the “voice of the duck hunter.”

Everyone Benefits

The State of the Birds report notes that “water birds”—a class that includes herons, egrets, and grebes—have also increased, up 18 percent since 1970 as a byproduct of hunter-driven wetland conservation efforts. And the continued success of aquatic wildlife is but a fraction of the myriad benefits of wetlands to society, such as improved drinking water quality and supply, flood control, erosion abatement, carbon/pollutant sequestration, and much more.

“Even people who spend their entire lives in cities are benefitting every day from duck hunter-initiated and -financed wetland conservation,” Petrie said. “For more than a century, waterfowl hunters have put their time and money where their heart is to protect wetlands and make ducks. And everyone in society benefits.”

Kyle Wintersteen of Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, is editor of Delta Waterfowl.