What's New

STAY UP TO DATE ON THE WORLD OF WATERFOWL HUNTING

Delta is your source for up-to-date news, podcasts, hunting strategies, recipes, duck dog stories, and hunting gear.

Delta Waterfowl Commends Make America Beautiful Ag...

2/12/2026

MABA 250 lays out a vision to promote stewardship of natural resources and expand outdoor recreation opportunities

Read more

Nova Scotia Hunters Celebrate Expanded Sunday Hunt...

2/6/2026

Delta Waterfowl championed a beneficial change to add 11 days to the duck season

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Boosts Mallard Numbers with Hen Ho...

2/4/2026

The Duck Hunters Organization plans to add 2,200 nest structures this winter in key breeding areas

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Receives $100,000 Grant from SCI F...

1/29/2026

Award supports Delta’s University Hunting Program to educate future wildlife managers about hunting and conservation

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Voices Support for Canadian Wildli...

1/23/2026

Proposals would increase opportunity, open new seasons

Read more

Find Ducks in the Late Season

1/20/2026

Ice and snow concentrates waterfowl and can make scouting easier. Here’s where to start your search.

Read more

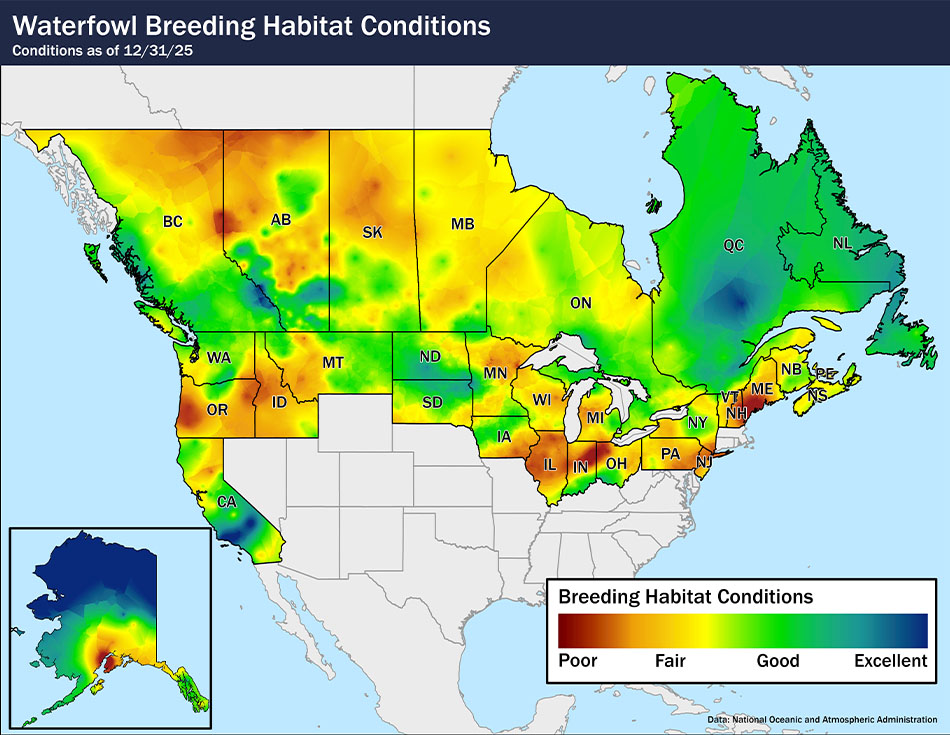

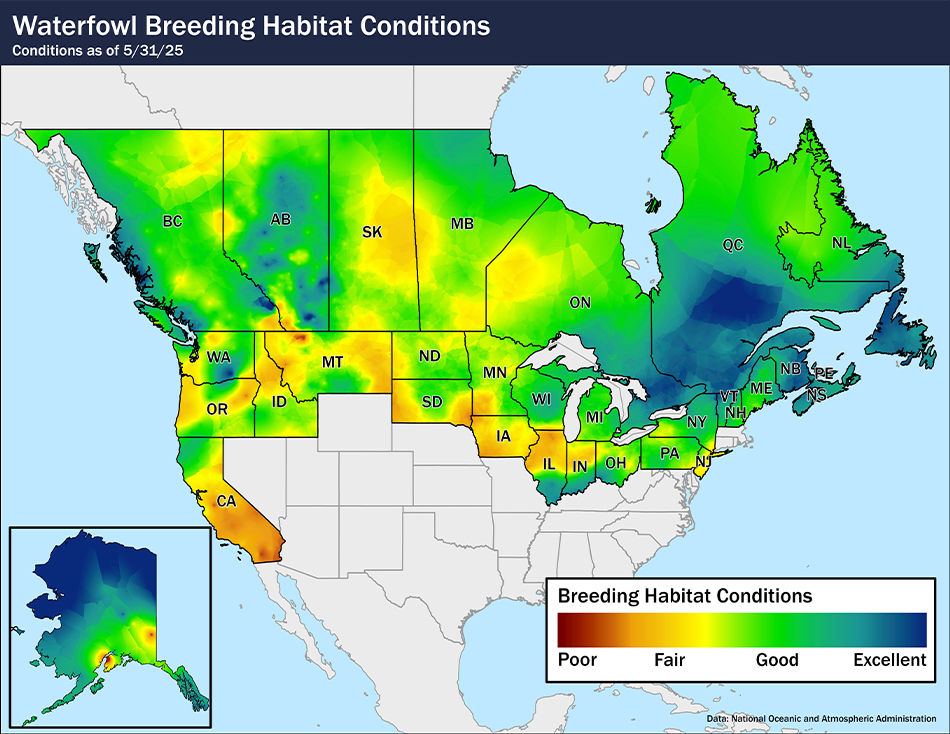

U.S. Waterfowl Breeding Conditions Primed for Spri...

1/15/2026

Western Canada remains in a prolonged drought, but there’s still time for more precipitation on the Prairie

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Applauds Secretary Burgum’s Order ...

1/14/2026

Action establishes an “open unless closed” stance for hunting and fishing

Read more

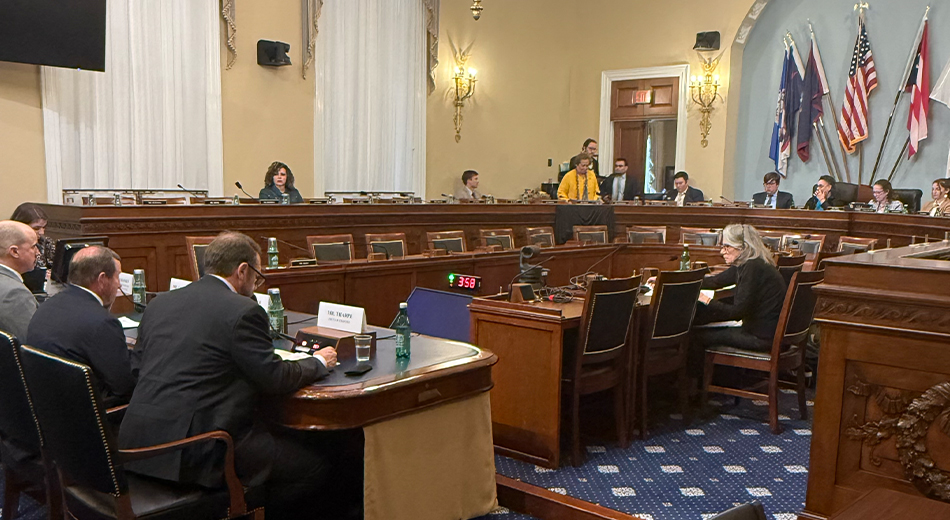

Delta Waterfowl CEO Testifies in Congressional Hea...

1/13/2026

Delta’s Jason Tharpe serves as a strong voice for ducks and duck hunters

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Volunteers Plug into the Public Ti...

1/9/2026

An Arkansas nonprofit is mobilizing duck hunters to improve neglected public lands

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Joins Partners to Advocate for Pub...

1/8/2026

Delta staff and volunteers participated in Camo at the Capitol Lobby Day in Madison

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Hires New Magazine Editor

1/7/2026

Illinois native Joe Genzel will lead the organization’s membership publication

Read more

A Christmas Tale: Break-In Day

12/17/2025

Christmas Eve in the duck boat sees peace on earth and good will to all — both lost and found

Read more

The Nomadic Northern Pintail

12/17/2025

‘Sprigs’ chart a wandering path shaped by early migrations, perilous nest options, and a changing landscape

Read more

Float Your Way to More Ducks

12/17/2025

There’s a simple pleasure to guiding a canoe into the water and allowing the current do the work — and it’s a great way to drop greenheads.

Read more

Chris's Gift Giving Guide

12/8/2025

If you’re still looking for the perfect gift for the waterfowl hunter in your life, check out the list below, provided by Chris Williams.

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Testifies in Support of Wisconsin ...

11/21/2025

Wildlife populations thrive when they’re managed by sound science, which includes sustainable harvest

Read more

Delta Waterfowl’s Winter Issue: Major Refuge Reviv...

11/19/2025

If you’re a member of The Duck Hunters Organization™, Delta’s final magazine of 2025 is headed your way

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Mourns Passing of Duck Calling Ico...

11/19/2025

Merle “Buck” Gardner, a world-champion duck caller and passionate supporter of waterfowl conservation, died Nov. 7 at his home in Memphis, Tennessee.

Read more

Protect Sensitive Ears

11/18/2025

Simple precautions can help your retriever avoid hearing loss

Read more

New Senate Stewardship Caucus to Protect and Expan...

11/18/2025

Vigorous Duck Production, HunteR3, and other Delta-supported efforts continue across the United States and Canada

Read more

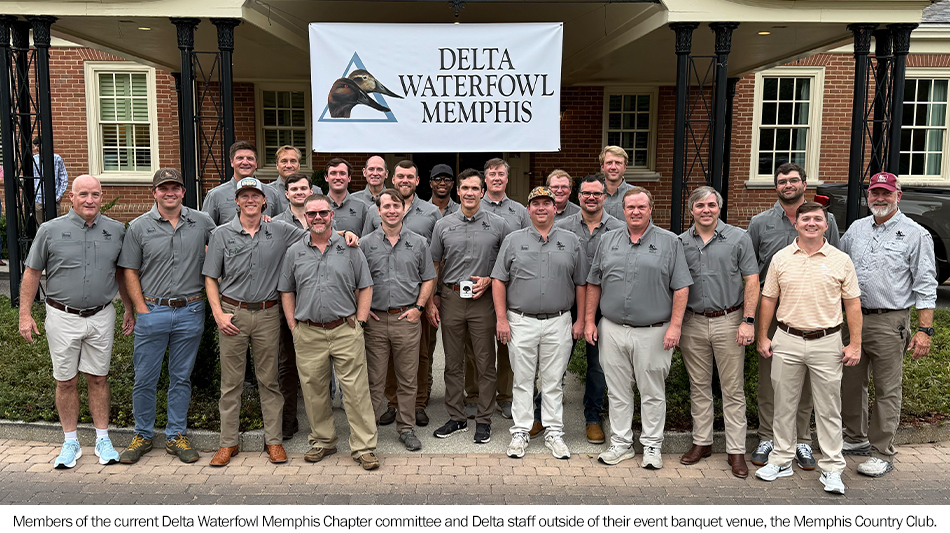

Delta Waterfowl’s Memphis Chapter Passes $3 Millio...

11/17/2025

With a record-setting 2025 banquet and decades of dedication, the chapter continues to lead in Delta’s fundraising network

Read more

Delta's Policy Work Boosts Quality Hunting Opportu...

11/14/2025

Delta Waterfowl works diligently to address threats to duck hunting and to create new opportunities throughout North America.

Read more

Restoring Our Refuges

11/14/2025

Delta's plan to recharge public habitat and revive waterfowl migrations

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Launches Major Initiative to Resto...

11/14/2025

Our goal is to improve waterfowl hunting throughout North America by investing more resources into public lands

Read more

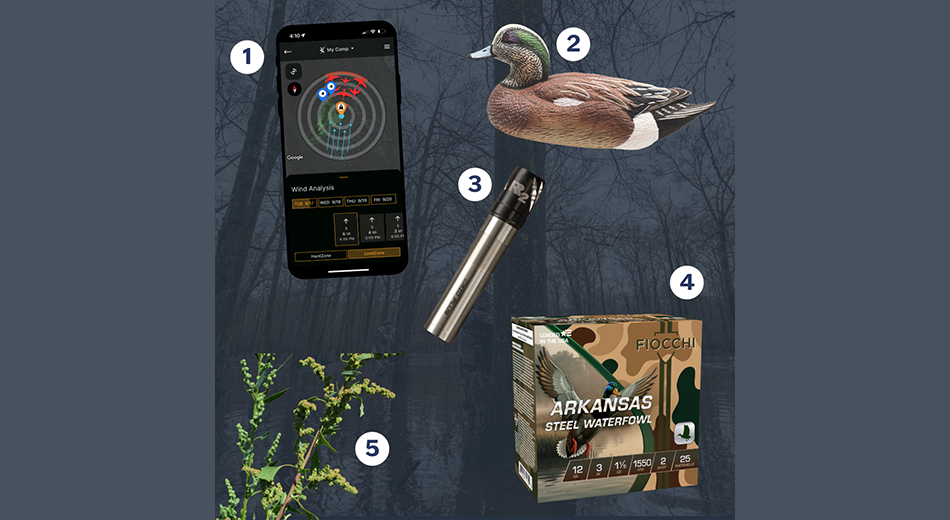

Fresh Finds for the Duck Blind

11/12/2025

Everything you need to make this duck season your best one yet.

Read more

Waterfowl Hunter Numbers Drop

11/4/2025

Reports reveal slight decrease from prior season, duck harvest also dips

Read more

The Well-Equipped Mentor

10/28/2025

The pros/cons of neoprene and breathable materials can help you find the right waders for you

Read more

Get Wader Wise

10/28/2025

The pros/cons of neoprene and breathable materials can help you find the right waders for you

Read more

Goose Groups

10/28/2025

Are you typically able to make an educated guess about where a flock of honkers flew in from? Or where they’re headed? See if you can match each goose

Take quiz

Connecting Through Conservation

10/28/2025

Delta Waterfowl staff, volunteers, and partners bring waterfowl science to special needs students in Pennsylvania

Read more

The Heart of Hunting

10/23/2025

A first hunt reveals the strange mix of joy and sorrow that can accompany a bird in hand

Read more

Feliz Navi-Duck

10/23/2025

Halloween, Thanksgiving, and Christmas carry added meaning for us waterfowlers

Read more

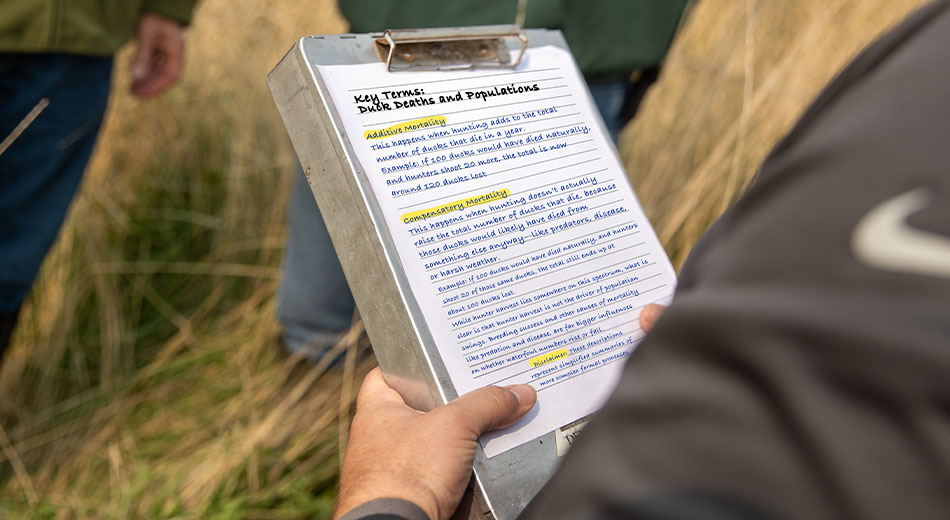

Hunt Ducks, Lose the Guilt

10/23/2025

What does the science say about the impact of hunter harvest on waterfowl populations?

Read more

Delta’s Meetings With the CEQ Chair and USFWS Dire...

10/22/2025

Vigorous Duck Production, HunteR3, and other Delta-supported efforts continue across the United States and Canada

Read more

California End of Legislative Session Summary

10/14/2025

Delta Waterfowl’s policy team had a busy and productive year in California. We engaged in a variety of bills from waterfowl conservation and wetlands

Read more

Wood Ducks on Purpose

10/8/2025

A focused approach to wood ducks demands tactics as unique as the birds

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Policy Work Helps Expand Sunday Hu...

10/6/2025

The Duck Hunters Organization™ advocated for regulatory changes that greatly increase opportunities for hunters

Read more

Home Sweet Homing

10/1/2025

Ducks retrace a successful route to enhance their odds of surviving and reproducing

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Urges Swift Action to Keep U.S. Go...

9/30/2025

Access to federal public lands is important for many waterfowl hunters

Read more

‘May I Hunt Your Land?’

9/26/2025

Gaining access to private ground takes luck, guts, and strategy

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Joins Forces to Launch Canadian Wi...

9/23/2025

Coalition will defend science-based wildlife management and protect the rights of hunters and trappers

Read more

Delta Waterfowl CEO Represents Duck Hunters at the...

9/19/2025

Delta’s Jason Tharpe met with Interior Secretary Doug Burgum during a conservation leadership forum on federal land management strategies

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Receives Grant for Habitat Conserv...

9/19/2025

Generous support will advance Delta’s policy efforts to keep at-risk shallow wetlands from being drained.

Read more

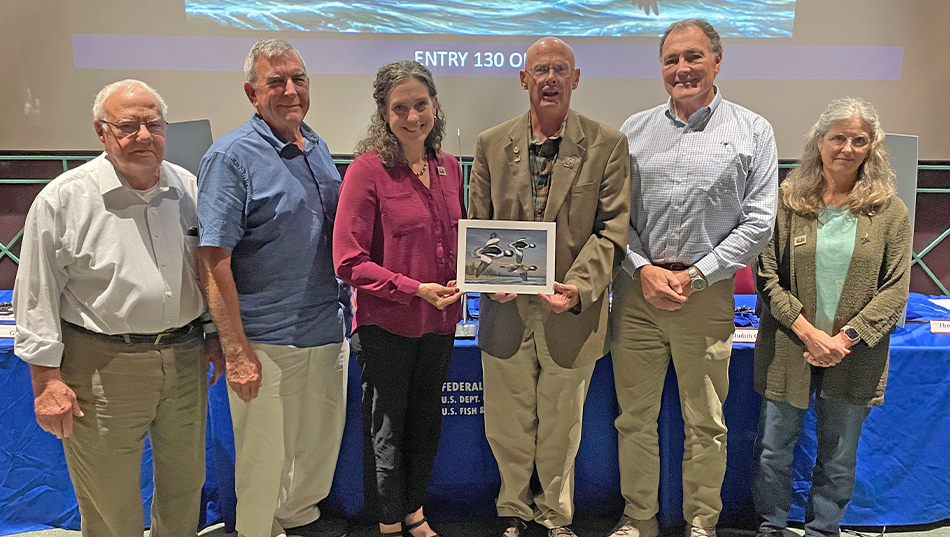

Delta Congratulates James Hautman on 2025 Federal ...

9/19/2025

The Federal Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp has generated more than $1.3 billion for conservation since 1934

Read more

Delta Waterfowl’s Fall Issue Forecasts Duck Flight...

9/18/2025

“The ducks just don’t migrate like they used to,” is a phrase that’s been uttered frequently in recent seasons. You may have even said it yourself. And at

Read more

Jump-Shooting with a Retriever

9/17/2025

Teach your dog special skills to go mobile for ducks

Read more

Winning the Early Season

9/17/2025

Fill duck straps this October by using these clever strategies.

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Hosts Inaugural ‘Duck Hunters Day’...

9/17/2025

Vigorous Duck Production, HunteR3, and other Delta-supported efforts continue across the United States and Canada

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Welcomes Development Director for ...

9/17/2025

Seasoned fundraiser Rhett Butler joins The Duck Hunters Organization™ to leverage support for ducks and duck hunters

Read more

Pintails Increase, Bag Limits Expected to be 3 Dai...

9/4/2025

The northern pintail breeding population estimate of 2.24 million is a 13% increase over 2024’s estimate of 1.98 million, according to the Waterfowl Popula

Read more

Ross’s Geese, AP Canada Geese, and Midcontinent Sp...

9/3/2025

Ducks might dominate the headlines when the annual Waterfowl Population Status Report is released, but the report also contains critical insights for the

Read more

Eastern Survey Area Duck Populations Remain Strong

9/3/2025

Results from the Eastern Survey Area are typically an underreported aspect of the Breeding Waterfowl Population and Habitat Survey conducted each spring by

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Reports: USFWS Annual Breeding Wat...

9/2/2025

Breeding population nearly identical to 2024, but dry prairie conditions likely suppressed duck production

Read more

Restoring Duck Distribution

9/2/2025

Delta is set to produce millions of ducks—and spearhead their return to traditional southern strongholds

Read more

Six Quick Tips for Scouting Early-Season Honkers

8/25/2025

Here are six quick tips to get you on the birds and keep you on the birds.

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Hires New Chief Development Office...

8/22/2025

Eric Lindstrom will lead fundraising team’s efforts to support conservation programs

Read more

How to Hit Teal

8/20/2025

SHOTSHELL MANUFACTURERS have no greater allies than blue-winged and green-winged teal.

Read more

Shotgunning: Barrel Length Ballistics

8/20/2025

Adding or decreasing a few inches of barrel can enhance wingshooting

Read more

Don’t Rock the Boat

8/20/2025

Preparation and training are critical to boating safely with retrievers

Read more

Delta Welcomes Kent Cartridge as Champion of Delta...

8/19/2025

Known for their premium waterfowl loads, Kent Cartridge is committed to giving back to waterfowl conservation

Read more

Positive Strides Towards Protecting Critical Wetla...

8/19/2025

Vigorous Duck Production, HunteR3, and other Delta-supported efforts continue across the United States and Canada

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Welcomes Regional Director for the...

8/15/2025

A South Dakota native, Blake Ketterling brings more than 20 years of fundraising experience to the role

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Promotes Baird to VP of Government...

8/14/2025

Cyrus Baird continues to push for increased conservation funding and quality duck hunting opportunities

Read more

2025 State Waterfowl Breeding Population Survey Ro...

8/11/2025

Spring duck numbers up in California, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, down in North Dakota

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Hires Talented Leader as VP of Mar...

8/7/2025

Minnesota native Mike Sidders aims to expand the reach and impact of Delta’s messaging

Read more

Delta Waterfowl’s Route 66 Chapter Helps Protect H...

8/7/2025

Thanks to local leadership and Delta policy support, public hunting will continue at Fellows Lake under a new blind draw system

Read more

Delta Waterfowl’s Newest Issue Celebrates a Millio...

8/6/2025

If you’re a member of The Duck Hunters Organization, then your favorite magazine of the year—the Delta Waterfowl ‘Hunt Annual’—arrives soon!

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Hires Two Premier Research Scienti...

8/5/2025

Dr. Todd Arnold and Dr. Jay VonBank add extensive waterfowl expertise and experience to The Duck Hunters Organization

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Congratulates Nesvik on Confirmati...

8/1/2025

The U.S. Senate has confirmed Brian Nesvik as director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Read more

Delta Waterfowl’s Fundraising Campaign Nets $284 M...

7/30/2025

Astounding success of the Million Duck Campaign will allow The Duck Hunters Organization to expand duck production and add 1 million ducks to every fall

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Honors Champions of Conservation

7/29/2025

Outstanding advocates help The Duck Hunters Organization fulfill the mission to produce ducks and ensure the future of waterfowl hunting across North Amer

Read more

Delta Expo Delivers on Promise of Duck Hunters Par...

7/29/2025

Expo attendees and industry partners brought excitement, enthusiasm, and camaraderie to the Oklahoma City Fairgrounds

Read more

Where Ducks Nest Impacts Production

7/29/2025

Across the breeding regions, various species of ducks each have preferred nesting locations known as core breeding ranges. Within these core areas, habitat

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Crowns Seth Fields as Winner of De...

7/29/2025

Handmade call brings home Delta Grand National Double Reed title for Tennessee native at the Delta Waterfowl Expo

Read more

Quiz: Do You Have ‘Duck Depression?’

7/29/2025

Face it: You aren’t you when it isn’t duck season. The air seems less crisp, daily life is downright monotonous, and your significant other

Take quiz

Duck Dog Tip: Preventing Heat Stroke

7/29/2025

Hot weather activities – whether training or hunting – can be dangerous for your duck dog if you don’t take proper precautions.

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Honors 2024-2025 Chapter Volunteer...

7/28/2025

The Duck Hunters Organization recognizes four outstanding conservation leaders for dedication to the mission to produce ducks and secure the future of

Read more

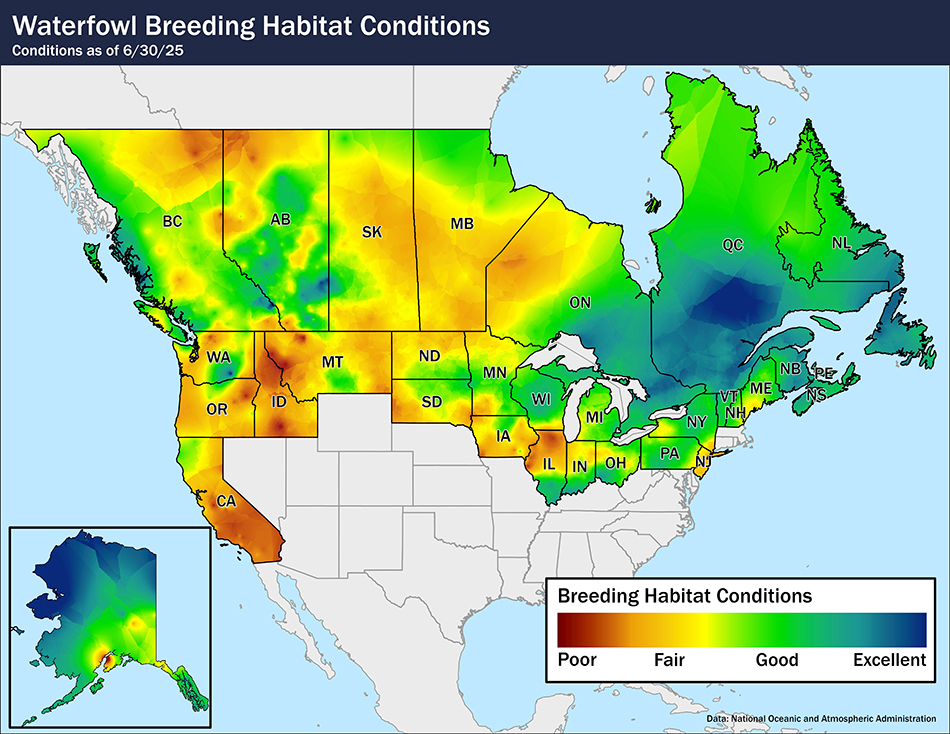

Waterfowl Breeding Habitat Conditions As of June 3...

7/28/2025

Delta Waterfowl’s latest data- and field-based assessments reveal a discouraging end to the 2025 duck breeding season across much of the prairie and

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Applauds Introduction of HEN Act i...

7/28/2025

Proposed law would authorize funding for duck production and habitat conservation efforts to increase waterfowl populations

Read more

A High-Mileage Mallard

7/28/2025

Alabama to the Arctic: Geolocator reveals hen’s wild journey north

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Applauds Alberta’s New Private Lan...

7/22/2025

Small wetlands are identified in the plan as a key conservation need

Read more

Delta Waterfowl Submits Support of USFWS Hunt Fish...

7/17/2025

Vigorous Duck Production, HunteR3, and other Delta-supported efforts continue across the United States and Canada

Read

Delta Waterfowl Double-Reed Calling Championship H...

7/14/2025

Presented by Drake Waterfowl and Mack’s Prairie Wings, the Delta Grand National will take place on Saturday, July 26, during the organization’s annual Duck

Read More

Delta Waterfowl Welcomes New Regional Director for...

7/11/2025

Ryan Sturm brings nearly a decade of dedicated experience as a Delta volunteer

Read More

Pennsylvania Repeals Sunday Hunting Ban

7/9/2025

New law doubles opportunities to hunt for people with busy lives

Read More

Delta Waterfowl Renews SoundGear as a Valued Spons...

7/8/2025

Partnership continues to advance waterfowl conservation, hunting heritage, and hearing protection in the field

Read More

Delta Waterfowl Names LaMontagne as Vice President...

7/8/2025

Previously serving as Delta’s director of development operations, Whittlee LaMontagne moves into an executive role to further amplify the organization’s co

Read More

Delta Waterfowl Names Lawrence Vice President of D...

7/8/2025

An integral addition to the organization’s executive staff, Lisa Lawrence joined The Duck Hunters Organization in 2007

Read More

Delta Waterfowl Duck Hunters Expo Kicks Off Later ...

7/8/2025

July 25 to 27 event in Oklahoma City features all things waterfowl, including live stages, expert-led seminars, innovative gear, and more

Read More

Delta Waterfowl Applauds Louisiana Governor and Le...

6/27/2025

Measures will restore and create critical wintering waterfowl habitat to attract and hold more ducks and geese

Read More

Waterfowl Breeding Habitat Conditions Update As of...

6/20/2025

Widespread rains during May—a critical month for duck production—brought welcome relief to much of the Prairie Pothole Region, particularly in parts of

Read MoreGet Involved

Check out all our upcoming events for a chance to connect with local duck hunters

Upcoming Events

MB006 - Winnipeg Whistling Wings Chapter

2/19/2026

Thursday, February 19, 2026 Winnipeg, MB

View Event